Does it really matter if the masterpiece you’re looking at is an original, or a copy, if it looks identical?

John Myatt argues it doesn’t. Indeed, he says the financial wheelings and dealings of the art world have distorted what counts, and that’s our aesthetic response.

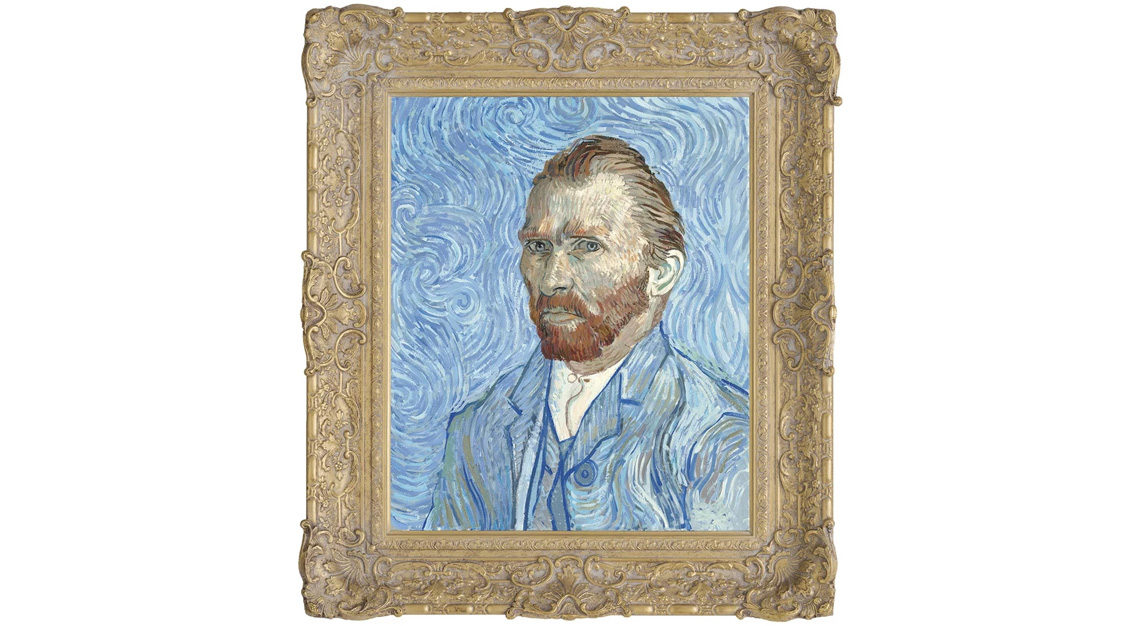

“Looking at what I call a ‘genuine fake’ is to give pleasure to the eye, to the intellect, to get that visual stimulus without it being stripped away by someone’s idea of the value of that item,” he says. “But, you know, the fact is that when you’re looking at, say, a real van Gogh, what you’re actually looking at is the money. You’re considering its worth, those millions of pounds. The art gets lost.”

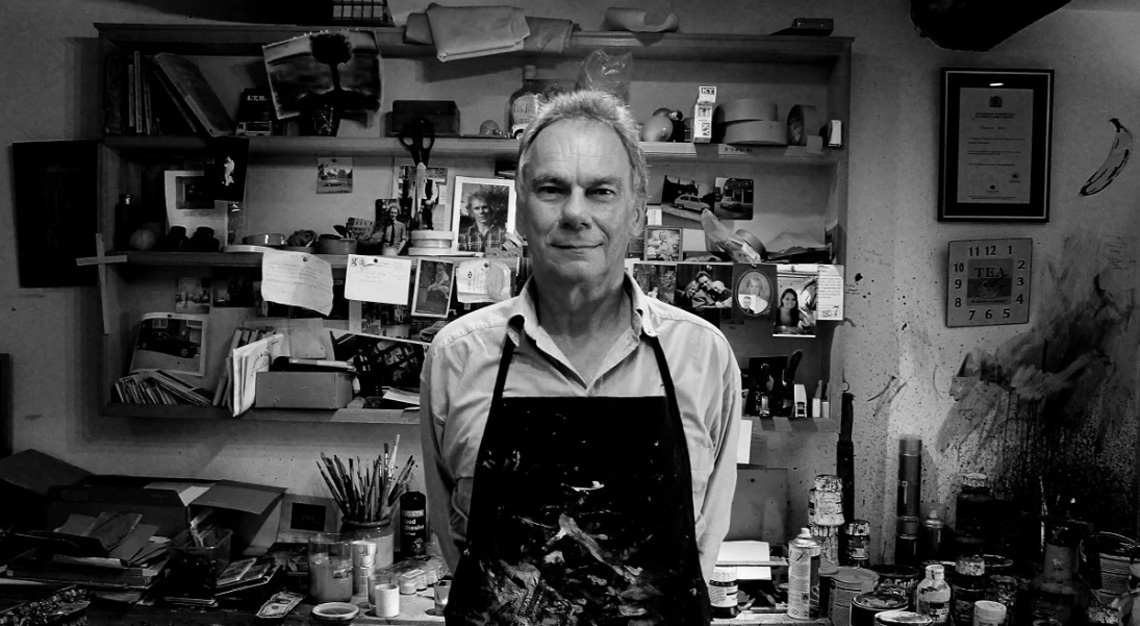

But then the London-based Myatt speaks from an unusual standpoint. He is a one-time art forger turned legitimate artist (he currently paints commissioned works and clear copies) whose celebrity as such now means that his own “genuine fakes” sell for up to US$39,150 (S$54,454) a piece.

During the ’80s, the then-art teacher began painting and selling above-board copies of famous paintings. One customer, John Drewe, became a regular, one day reporting back that he had managed to sell one of Myatt’s works through Christie’s auction house for £25,000 (S$45,187). The game was afoot. Over the following years, Myatt and Drewe – the real talent behind the fraud, if not the art – passed off some 200 paintings as genuine. Myatt was arrested in 1995; in 1999, he was sentenced to a year in prison for conspiracy to fraud (he was released after serving four months).

The art world doesn’t like to talk about it – it is a dent to both its credibility and the marketability of its product – but it is flooded with fakes. The last couple of years have seen a spate of incidents revealing works displayed even by major museums to be forgeries.

Genoa’s Palazzo Ducale found that 21 Modigliani paintings it had on show were forgeries – Modigliani fakes are so numerous, in fact, that a proper cataloguing of his oeuvre is next to impossible. Ghent’s Museum of Fine Arts had to remove 26 works by Kandinsky and Malevich after they were uncovered as fakes. The Musée Terrus in Elne, France, discovered, no doubt to its horror, that more than half of the 140 Étienne Terrus paintings it was preparing for an exhibition were forgeries.

A 2014 report by the Fine Art Expert Institute estimated that over half of the artwork in circulation are fake. That more mid-level art is increasingly sold via the internet has only opened up another huge channel through which forgeries flourish. No wonder, given the skill of forgers today.

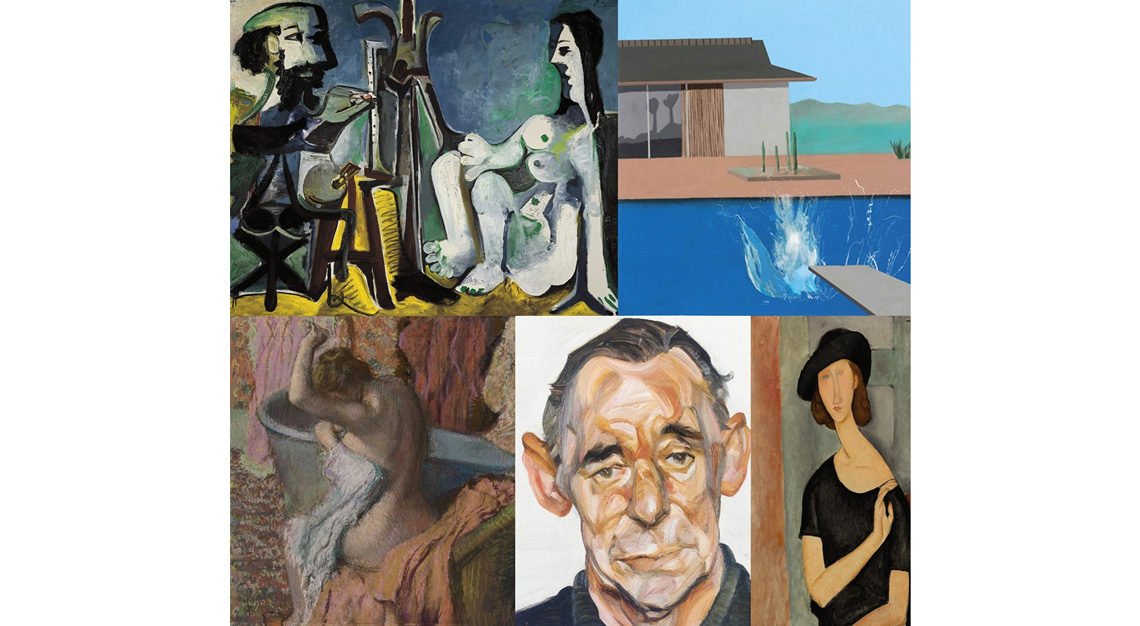

“It’s all about close study, through which you develop a feeling for an artist – down to the thickness of the paint they use, their characteristic stroke, with the kind of brush they likely used,” says Myatt. “That study gives you the tools you need. Then it’s a kind of reverse engineering. Of course, none of this engineering you come to understand has anything to do with the feeling that inspired the original work, which is where the real artistry lies.”

Frankly, Myatt contends, there’s a tendency for people in the art world – buyers and sellers alike – to not really want to know the truth. Providing blind eyes are turned, and there’s an unspoken agreement that a painting is “original” – even if some digging would make that claim suspect – then the mechanism by which money can be made can continue to function.

“There are huge sums of money involved [in art sales], and the more art becomes something people invest in, rather than enjoy, the more they’re reluctant for the authenticity of that asset to be questioned,” Myatt argues. “The art world is still effectively an honour system, operating on the basis of trust.”

In other words, it depends on, and preys on, very human emotions – which is why Han van Meegeren, considered one of the 20th century’s greatest forgers, was able to have his Vermeer copies authenticated by the world-leading Vermeer scholar Abraham Bredius; Bredius, he knew, had always argued the Dutch master had had a religious period, so van Meegeren showed him a religious “Vermeer” painting.

It’s a story with a lesson well-heeled art buyers, desperate to own a certain piece, might be wise to take on board.