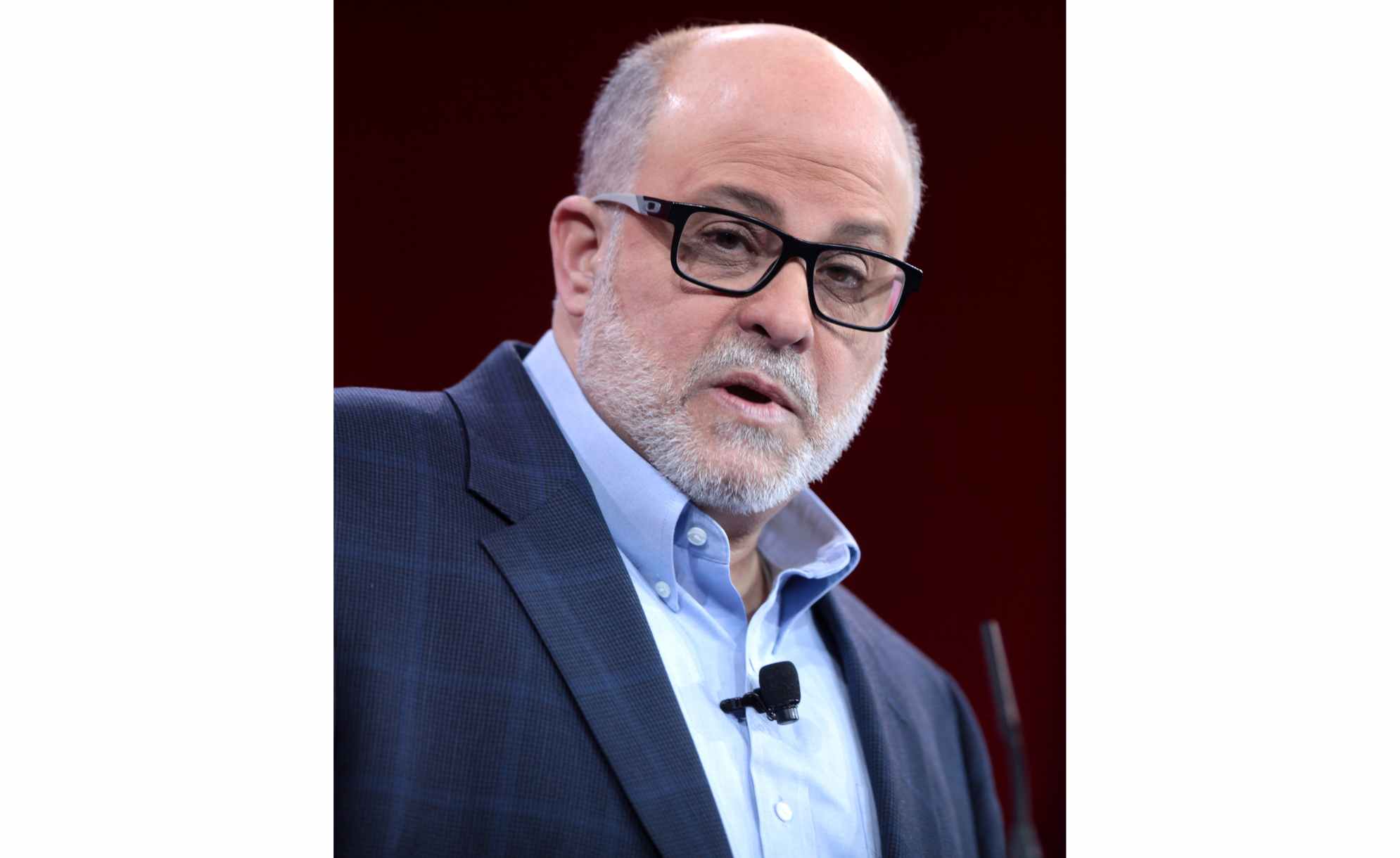

The Unfreedom of the Press takes a trip across the cobblestones of history to deplore the dearth of honesty and objectivity in the press

A free press is hailed as one of the great defenders of a free and democratic society. However, as I made my way through Mark Levin’s bestselling new book, the Unfreedom of the Press, one conclusion became depressingly clear: since its genesis in the 1600s to the present day, the press has never stopped being a weapon for politics.

Politics and their underlying ideologies have always come first for the press. After having played a key role in bringing an embryonic American Revolution to term, ideologues have continually sought to replicate their success in using the press to steer the unenlightened masses onto the “right” side of history. Compared to a greater good, honesty and objectivity have almost always taken a back seat. No tragedy yet has been too great to be brushed under the carpet when they come into conflict with political or ideological interests. Even two of the greatest European atrocities of the 20th century: the Holodomor, and the Holocaust, were wilfully underreported and downplayed by the free press when the catastrophes were well underway.

The press that we recognise as “free” today is a selective breed, an industry shaped through periodic culls by overzealous governments over the centuries. Countless news outlets have been brought to heel through the use of regulation, domestic espionage, blackmail, intimidation, and false imprisonment. These efforts continue on to the modern day, where even the Obama administration – which had one of the warmest relationships with the press in recent history – sought to implant government appointed “monitors” within newsrooms, so as to veto news pieces that promoted wrongthink.

But as with all sheltered purebreds, the press is now suffering from a crisis of diversity. Ideological inbreeding has led to an overwhelming concentration of liberals in the industry – in fact, during the 2016 US presidential election, 96 per cent of all financial donations made by individuals working in the press, went to the Clinton campaign. Dislocated from the spectrum of opinions that exist in the real world, the modern free press is stodgily anchored to their liberal attitudes and doggedly pursues an agenda of fomenting a resistance against the Trump administration and their supporters.

And in a staggering parallel to the persistent news coverage on Donald Trump’s alleged collusion with Russia, Mark Levin notes that one of the giants of the democratic party, Ted Kennedy, reached out to Yuri Adropov, the Secretary General of the Communist Party, in the 1980s. In his missive, Ted Kennedy requested Soviet support for his forthcoming presidential bid, in order to keep the “belligerent” Reagan from another term. Yet after the wall fell, and the once-confidential memos began pouring out of the remains of the Soviet Union, the press approached the matter tepidly, with nary a condemnation. Ted Kennedy remained a towering figure within the Democratic party and retained his seat in the senate for another 18 years until his death in 2009.

Maybe it is too much to ask for journalists and the news media to leave their hearts at the door, especially when it comes to politically and ideologically charged subjects. Just as how almost all of us are loathe to defend the dangerous and socially irresponsible anti-vax movement, or the growing amounts of plastic in our oceans, I imagine that a western liberal journalist must feel morally obliged to report negatively on the current US administration’s stance on illegal immigration and border control – or any other polarising policy for that matter.

So, where does this leave us? Outside of the suggestion that journalists exercise superhuman restraint to keep their reporting fair, balanced, and honest, the Unfreedom of the Press gives few answers. Instead, it prefers to portray itself as more of a catalyst for debate, rather than a panacea for the problems plaguing the free press. This left me rather unsettled – after all, I hail from Singapore, a country that has been characterised for almost all of its history as being particularly hostile to press freedom. If this institution, supposedly the bedrock of a well-oiled democracy, has in fact been so incredibly inefficient and corrupt throughout history, which model should we aspire to, in our quest to mature and evolve as a democratic society? Surely, shedding an overtly state-owned press for a surreptitiously state-owned press is not the answer.

Perhaps then, the path into the future lies in the hands of new media. For even if we cannot wrench journalists free from their inherent biases and ideological leanings, the internet may present a large enough frontier that governments find it effectively impossible to control the narrative in its entirety. Then, the only thing that’s left is for us to accept that there is no singular, default, authoritative news source. That reality has been, and always will be:

A kaleidoscope of grey.