Before there was Supreme or Off-White, there was the visionary Black designer’s WilliWear

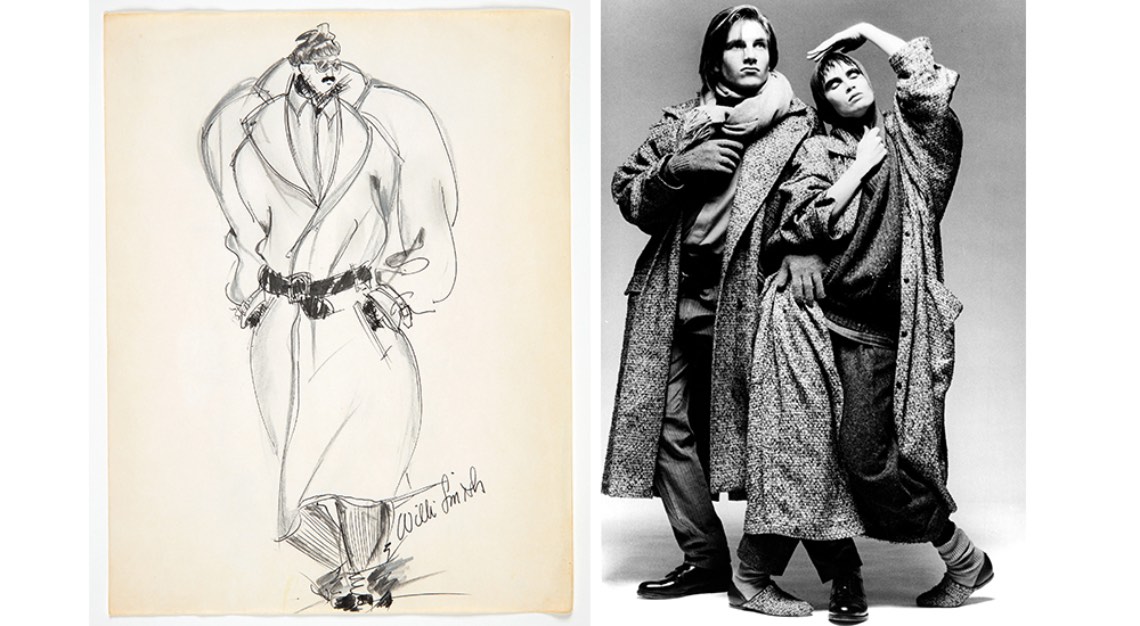

1983 was a major year for Willi Smith. That September, the New York City-based designer won the Coty American Fashion Critics Award for Womenswear – only the second Black designer to do so; when he was first nominated in 1967, he was the youngest designer ever in the running for the prestigious title. The same year, Smith also designed his Street Couture collection, drawing on hip hop elements like the graphics-laden clothing worn by break-dancers and B-boys as well as baggy, zoot suit-inspired tailoring. The name of that range became the term most frequently associated with the designer, a grandfather of sorts to the streetwear movement we know today.

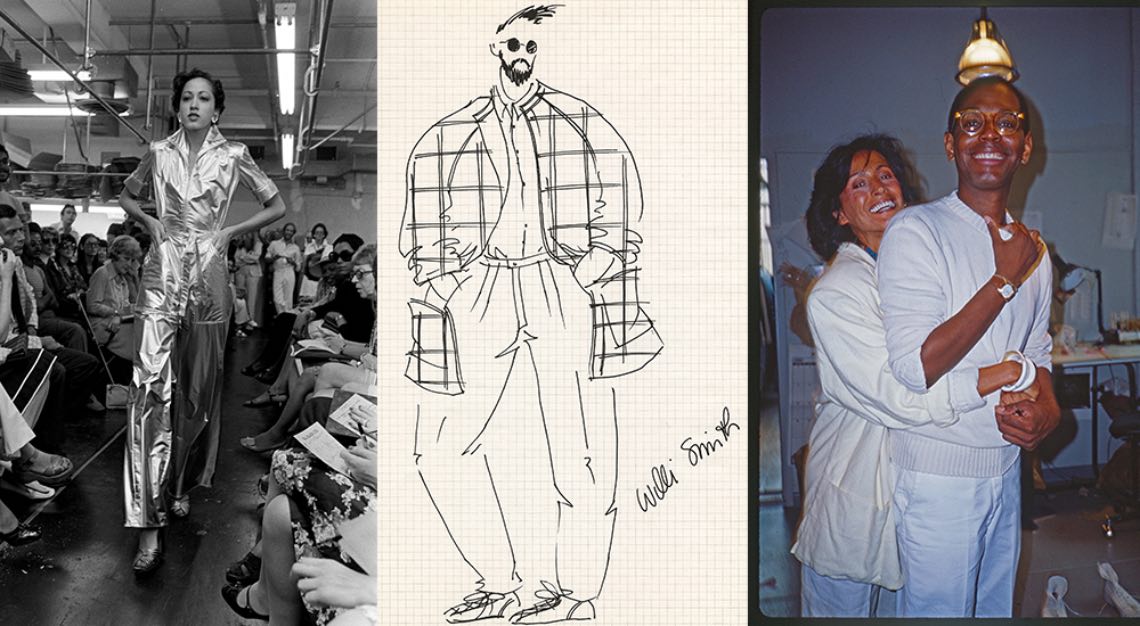

According to a 1983 People magazine article, Smith’s brand employed 85 people and shipped its men’s and women’s lines – WilliWear is credited as the first brand to encompass both under one label – to more than 1,000 department stores nationwide. A year later, the company was grossing some US$25 million (S$33.03 million) annually (over US$55 million/S$72.66 million when adjusted to today’s figures) and embarked on the first artistic collaboration of its kind with the likes of Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger and Keith Haring creating widely accessible designs. And yet for many who weren’t alive at the time of Smith’s massive success, his name was a mystery before 2020.

“He was one of the most successful designers [of his] time, both commercially and creatively,” Steven Kolb, president of the Council of Fashion Designers of America, tells Robb Report. Smith was also once called “the most successful Black designer in fashion history” by the New York Daily News. Kolb first came across the brand’s designs in the pivotal year of 1983, finding pieces at an outlet in Secaucus. “He came to be in a time when fashion was thriving and there were so many brands dominating the business: Ralph, Donna, Calvin among others. They became the story.”

But last fall, Willi Smith: Street Couture, a retrospective exhibition at the Cooper Hewitt museum, reassessed the designer’s impact on the history of fashion. Of Smith’s renewed accolades, Kolb says “It is good to see young people discovering WilliWear today and to see him get the attention he deserves.”

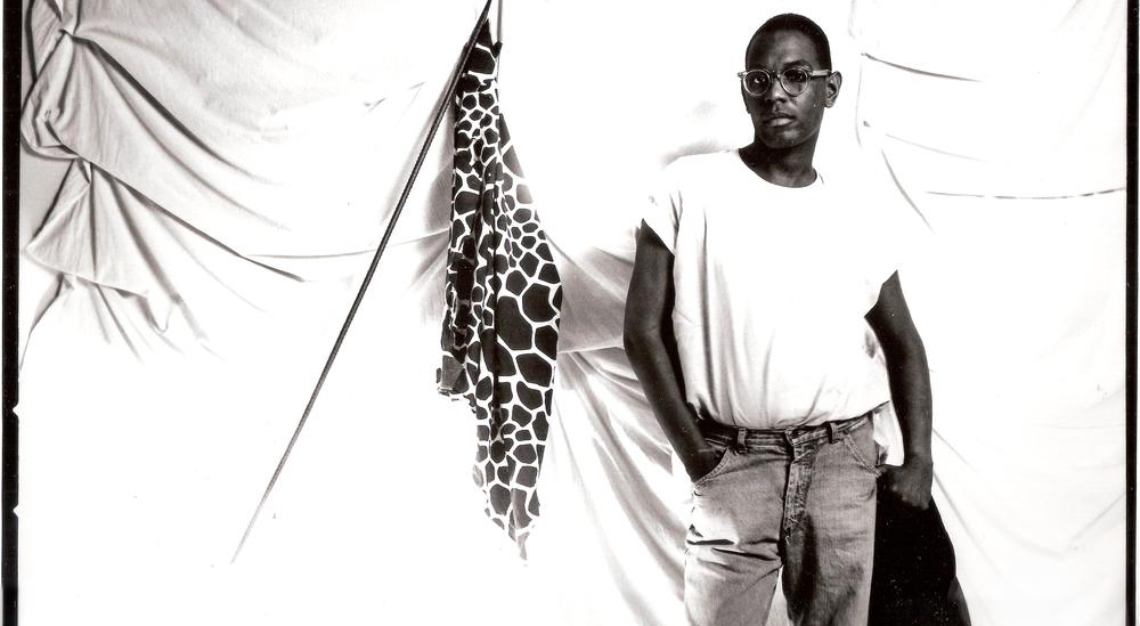

Smith was born in 1948 and grew up in Philadelphia. He was an artistic child, going on to study commercial art at Mastbaum Technical High School and fashion illustration at Philadelphia Museum College of Art. His first “break” came through his grandmother: She worked as a housekeeper and, through one of her clients, got her grandson an internship in the atelier of Arnold Scaasi, a favorite of mid-century grande dames like Brooke Astor and Elizabeth Taylor. While this wasn’t the career that Smith would beat out for himself – he famously said: “I don’t design clothes for the queen, but the people who wave at her as she goes by,” – it gave him a first-hand look at the industry’s inner workings.

In 1965, Smith applied to Parsons, the esteemed New York City design school. According to Cooper Hewitt exhibition, Camilla Hedger Lembo, an assistant in Parsons’ admissions at the time, called Smith “the most talented fashion-design applicant she had ever seen.” He was accepted with two scholarships but expelled two years later, allegedly for having an affair with a male student. That did not stop him. In fact, Smith would later return to those halls to lecture young students.In the years to follow, Smith made his name in sportswear. He was a part of both fashion’s “youthquake” and a wave of young Black designers, like Stephen Burrows and Patrick Kelly, who were making moves in the international scene. Smith, however, stood out from the pack for his democratic approach. In 1976, he opened a showroom for WilliWear, a brand that, in many ways, preempted much of what we see in the fashion business today.

“When I arrived at Barneys in the mid-80s, Willi was an important part of the product mix,” says Simon Doonan, former creative ambassador-at-large for the agenda-setting department store. Smith had developed a reputation for eclectic, irreverent takes on streetwear in washable fabrics and gender-neutral silhouettes. “His clothes had a freshness and lightness to them, which was very different from the more serious European designers.”

Breaking from the fashion designer archetype – the high-minded aesthete, creating in an ivory tower – Smith drew his inspiration from everyday life. Bethann Hardison, a close friend who also served as Smith’s fit model and was “discovered” by the designer, has often explained in interviews that if she wore something that Smith liked, he would ask her to take it off immediately for him to begin iterating designs on. In Cooper Hewitt’s Willi Smith Community Archive, Vijay Agarwal, a manager of WilliWear’s Mumbai factory, recalls driving in Bombay with Smith when the designer suddenly asked for the car to be stopped and for Agarwal to buy the shorts off of a traffic policeman. The resulting design, according to Agarwal, “went on to become one of his best-selling shorts in the early years.”

Smith’s genius wasn’t just being inspired by the street, but marketing and selling to it as well.

“What Willi did well before many designers was to speak to a mass customer base,” Kolb says. Smith even produced sewing patterns so that anyone could reproduce his collections at home. As Kolb notes, “The price point made it accessible and the design made it fashion, so his clothes were worn by a range of people who might not otherwise be connected.”

WilliWear’s fashion shows were more theater than conventional runway, which, along with Thierry Mugler and Franco Moschino, presaged today’s catwalk spectacles. Smith had a penchant for casting dancers to walk in his presentations – he once showed a collection on the dancers at Alvin Ailey – and even made fashion films.

There are many contemporary designers that are spiritual descendants of Smith. Brands like Kith, Off-White and Supreme can all trace lines back to the designer’s knack for grassroots buzz and pioneering collaborations. He was the first to team up with fine artists, putting works by the likes of Kruger and Haring on T-shirts that sold for the very democratic price of $37. He designed pieces for several of Christo and Jean-Claude’s monumental public art installations—even creating merch for them—and costumes for Spike Lee’s School Daze.

Designers like Hood By Air, Telfar and Eckhaus Latta can find a connection in Smith’s ideas around affordable luxury as well as his irreverence toward gender. He certainly pierced culture: New York City mayor David Dinkins proclaimed February 23rd Willi Smith Day in celebration of the designer’s many accomplishments. But after Smith died in 1987 from AIDS-related complications, his legacy was mostly forgotten.

“Over the past three decades since Willi’s death, I watched an enormous multibillion-dollar streetwear trend gain a grip on America. I always knew where this came from,” Kim Hastreiter, a founder of Paper magazine and close collaborator to Smith says in the Cooper Hewitt exhibition catalog. “Streetwear never really existed until Willi invented it.”