It’s impossible not to get inspired in this bastion of art and culture

Editor’s note: See other Escape Plan stories here.

Venice is a city that knows the importance of first impressions, On the day of my arrival one mid-January afternoon, I could feel it laying on the charm the moment I stepped out of the airport.

In time to a rhythm its waves slapped against the pier, the blue-green waters of the Venetian Lagoon greeted me with a shimmery dance under the soft glow of the winter sun. Uncooperative gulls bobbed lazily on the water’s surface in various stages of sleep, breaking up this enthusiastic display. At the urging of my approaching water taxi, they roused and took off screeching—a reluctant welcome wagon announcing my arrival.

As the avian fanfare built up in a crescendo, the Grand Canal rose into view on the horizon. Nameless romanesque, gothic, and renaissance buildings came into sight, forming a valiant barricade along the waterline. Centuries of determination showed through in the weathered reds, beiges, and pinks of their facades.

These used to be the palazzi, or palaces, of the rich and famous in Venice—relics of a time when anyone who was anyone had to broadcast their status with a prestigious canal-side address. But I’m not of that time, and as an irreverent modern observer, I thought it rather bold of the ancient Venetians to declare their residences palatial when the real deal’s just down the street.

Like the Doge’s Palace, easily identified by the pomp of its generous width, which is at least twice that of the palazzi that flank it. Standing behind is the bell tower of St Mark’s Basilica, lofty and slender, and an antithesis of the palace in every way. On the opposite bank, the Santa Maria della Salute Basilica vied for my admiration by thrusting its magnificent domed roof skywards.

I am not the first to wax lyrical about the showy welcome that Venice has extended to every visitor since time immemorial. As Claude Monet once said during his stay in the autumn of 1908, “It is too beautiful to be painted! It is untranslatable!” Now, more than a hundred years later, I am retracing the great artist’s footsteps.

A little past the Doge’s Palace and directly across from the Santa Maria della Salute Basilica, my water taxi chugged to a stop. I stepped off the boat onto a jetty, likely at the same spot where Monet disembarked every day after his sunset gondola ride.

In front of me stood a whitewashed palazzo. The artist knew this place as The Grand Hotel Britannia, his temporary abode during his 10 weeks in the city. Today, it is known as The St Regis Venice, my home for the next two nights.

A rebel in disguise

Venice is a renaissance dream caught in limbo; a city that shouts its bygone glory days from its authentically dated rooftops. And why not? It is what the tourists want and have come to expect. Not every city gets the privilege to age so gracefully.

By all appearances, The St Regis Venice plays along well with the city’s narrative. Housed in a collection of five palazzi, the oldest of which is the 17th-century palazzo Badoer Tiepolo, the hotel doesn’t stand out from the rank and file. Look beneath the surface, however, and the property would give a very different impression.

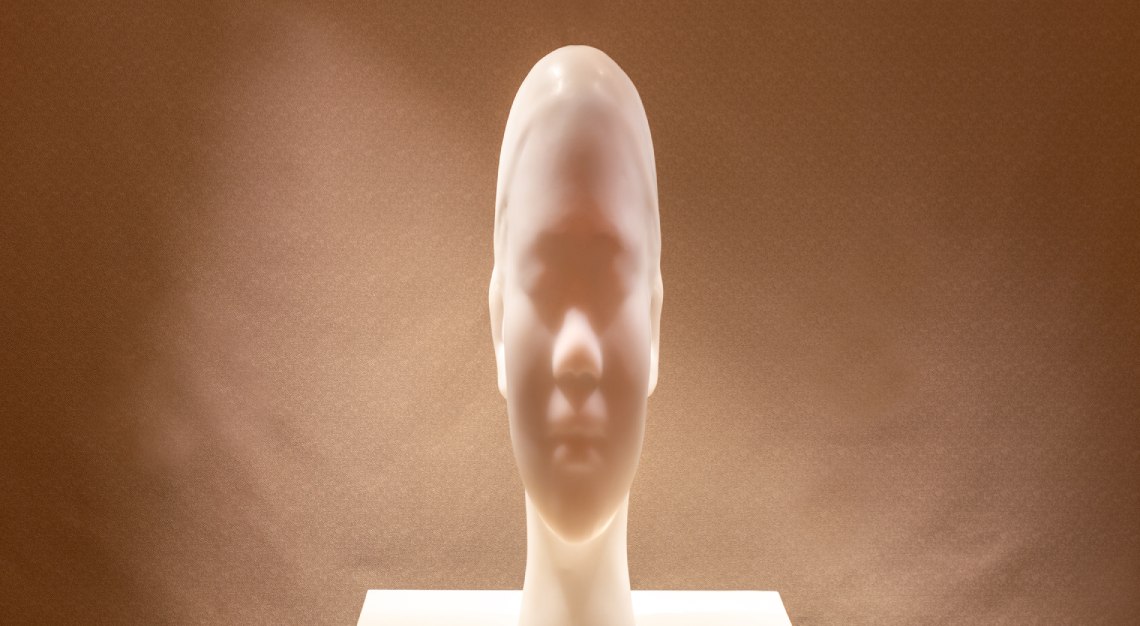

The devil’s in the details. In the Grand Salone, a mammoth glass chandelier hangs, taking up more than half the vertical space between the ceiling and the floor. At a cursory glance, it resembles a tangle of flowering vines, its ornate curves vaguely baroque in style—as befits a Venetian Palazzo. But study it a little longer and you’d spot unexpected details: crabs scuttling over the delicate flowers, a pair of handcuffs dangling from a branch, Twitter’s bird icon making a home among the vines, and perhaps most jarring of all, a hand with a raised middle finger. This is Chinese artist and activist Ai Weiwei’s iconic White Chandelier, created last year in collaboration with Murano glassmaker Berengo Studio as a site-specific artwork for the hotel.

A raised middle finger is always a statement. Here, it makes clear that The St Regis Venice is a space for experimentation, letting creativity run wild, and perhaps even a little rebellion. The hotel is cultivating the vanguard of the arts (as it proudly claims on its website), with curation helmed by Dr. Gisela Winkelhofer of art consultancy firm Edition ArtCo.

More recently, the public spaces of the property were taken over by growths of pink amaranth flowers that floated like ethereal imitations of weeping willows above paintings and wall sconces. They were part of an unconventional festive installation by Berlin-based floral design studio Mary Lennox. In addition to the floral sculptures, the studio also created cloud-like compositions that, upon closer inspection, revealed themselves to be made up of more than 10,000 glass Christmas ornaments. The installation was still up when I visited in January, which worked since the baubles weren’t in traditional Christmas colours anyway.

Every new turn I made in the hotel felt like walking into a different art gallery. Display cases lined the walls of the corridors at regular intervals, mostly displaying glass art. The St Regis Venice has a special working relationship with Murano glassmaker Berengo Studio. Founded only in 1989 by Adriano Berengo, Berengo Studio is a relatively young establishment among the Murano glassmakers with a modern approach to glassmaking that makes it a trailblazer in its own right. The studio is known for its bold collaborations with artists from various disciplines; Ai’s White Chandelier is one example.

In a hallway leading to Gio’s Restaurant & Terrace, the property’s main dining establishment, I encountered Esther Stocker’s Untitled. The Italian artist has a penchant for the abstract and geometric, as well as a monochromatic palette of black, white and grey. Her work is usually a commentary on systems—the precision (hence the geometry), as well as the ambiguity of them. Her installation at The St Regis Venice resembles canvases of her geometric works wadded up into balls, the crumpled forms introducing an aberration to what was originally an ordered visual rhythm.

Remembering the original vanguard

Before it took a raised middle finger to create shock value, all the Impressionists had to do to shake things up was to use a little more colour and a little less restraint in their brushstrokes. As a pioneer of the movement that is now widely considered a catalyst of the development of modern art, Monet was undoubtedly the original vanguard.

When the artist arrived in Venice in October 1908, he had expected it to be a non-working short vacation. The city was, after all as he proclaimed, so beautiful that no painting could do it justice.

But Venice’s beauty proved too irresistible. The artist’s short vacation stretched into 10 weeks, during which he stayed in one of four canal-fronting suites on the first and second floors of palazzo Badoer Tiepolo. It was here, before one of the Juliette balconies, that Monet sat, studying the changing light of the city over the course of the day. Despite initially having no intention to pick up his brush, he went on to produce 37 canvases on the trip. Today, the four suites have been named the Monet Suites in honour of the artist’s stay.

The spirit of Venice is captured in the design of the suites. It can be seen in the mouldings of the entrance doors, which call to mind the pattern of the city’s footpaths. The shape of the arms of the dining chairs were inspired by the forcola, or rowlock that supports the oars of a gondola.

Of course, there are many references to the suite’s namesake. The soft gradient of colours in the rugs imitate the brushstrokes of Monet’s paintings. Adorning the walls is a series of commissioned works titled Hommage à Monet by the hotel’s first resident artist, French painter Olivier Masmonteil. Following in the impressionist master’s footsteps, Masmonteil, too, endeavoured to capture the special light of Venice, but in a contemporary language that is uniquely his own.

A taste of art

As the clear blue of the day shifted into the pastel pinks, peaches, and purples of sunset, I headed down for an aperitif. The Arts Bar is located on the ground floor of palazzo Barozzi, once home to the small but well-regarded San Moisè Theatre. The highlight on its menu is the selection of craft cocktails inspired by renowned artworks that have a known association to Venice. Each drink is served in custom-made glassware by Berengo, of course.

I was tempted by the look of Canal Art, a drink inspired by the graffiti that mysteriously appeared on a building during Venice Biennale 2019. The work showed a child in a life jacket holding up a pink flare with one hand. Eagle-eyed art lovers who spotted the graffiti believed it to be a statement on the refugee crisis by Banksy, although the English artist never came forward to claim it.

In its alcoholic incarnation, the artwork is a mezcal-based cocktail topped with a generous swirl of baby pink foam. The drink draws parallels between mezcal and Banksy: they both have a strong personality and share anonymity; mezcal, because it has yet to gain traction outside of Mexico, and Banksy, by choice. Besides the mezcal, flavour also comes from the cordial, which is made from artichokes grown on Sant’Erasmo, an island in the Venetian Lagoon. The foam is flavoured with a spray of saltwater to recall the waters of the Grand Canal.

At the encouragement of my sweet tooth, I passed on Canal Art for Venetian Cobbler, a cocktail that takes the imbiber back more than 400 years to 1548, when Jacopo Tintoretto’s The Miracle of Saint Mark was completed. Tintoretto, widely considered one of the most important names of the Venetian school, is an art movement developed in renaissance Venice that is marked by exuberant colour, over-embellishment, and a tinge of hedonism.

The Miracle of Saint Mark was based on the famous story about a slave who disobeyed his master to go on a pilgrimage to Venice. He was captured and tortured till Saint Mark came to the rescue. The painting depicts the moment when Saint Mark, summoned by the invocations of the desperate slave, appears as an apparition. He destroys the instruments of torture and frees the slave while the astonished crowd watches.

Like one of the gawping spectators in the painting, I sat by and watched as the drama unfolded. The cocktail was delivered smoked under a dome, the rich grape flavours and dark red colours of valpolicella wine and fino sherry mirroring the slave’s crimson robes. The painting’s indentured protagonist was swarmed by an audience at the scene; I witnessed a drink barely visible under the shroud of green tea smoke. Then, the dome was lifted; Saint Mark had arrived. The smoke dissipated to reveal my drink, just as the slave’s tormentors were compelled by a supernatural force to release their hold on him. He was finally free to go, and I, to sip.

As the housemade strawberry shrub in my cocktail released a burst of fruity, sweet and sour flavours, I marvelled at how the mixologist has managed to make a crash course on renaissance art taste so good. It must be the Venetian charm; the same charm that gave Monet the impetus to paint, and me the inclination to add to the already abundant literature on the city. It’s the special hold Venice has on those who call themselves creatives.