Michelangelo Pistoletto may be 85 this year, but the jovial Italian artist – most known for his Third Paradise symbol and mirrored ‘self-portraits’ – is still firing on all cylinders

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJ3AfGphAIw

There aren’t many people who can carry off a purple fedora, but Michelangelo Pistoletto is one of them. He wears it as he does his slightly baggy black suit; without a hint of irony, every inch the artist in attendance. His 85-year-old body, despite sporting the ravages of time, has a curious jauntiness. It was always going to be a challenge interviewing a man described by many as one of the greatest conceptual artists of his generation. One imagines that coming up with a question he hasn’t been asked a thousand times will be difficult, while something completely out of left field could irritate, alienate and cause hackles to rise.

We exchange chairs before ‘rolling’ – his was the comfortable one into which he sank almost instantly and looked ill at ease. Mine was more obdurate, with a straight back that gave me an elevation that intuitively felt wrong. We swapped.

“Do you dream in colour or in black and white?” I ask.

“Both,” comes the instant response. “I dream about the ‘new cinema’ that is created in my mind. Basically, all my work is done by my dreams in the night. Not exactly in the dream, perhaps, but at the moment when you stop dreaming and are awake again. The dream is a kind of preparation, a formulation of the problem, and the reawakening opens up the opportunity to a new way of thinking.”

My opening gambit has failed to shock or even surprise. It’s time to get on to safer territory.

It Runs In The Family

Pistoletto was born in 1933, and his father was an artist with his own art restoration business. His mother was, for a time, one of his father’s pupils. He served an apprenticeship of sorts in his father’s workshop, and was exposed to many different classical forms of art that informed his progress as an artist. It made him realise what kind of artist he didn’t want to be.

While enjoying his experiences with the still lifes, landscapes and Byzantine icons, on an unconscious level Pistoletto must have realised that he was already headed in a different direction; something that engaged the viewer on a deeper, more provocative level, stimulating the imagination through multisensory experiences.

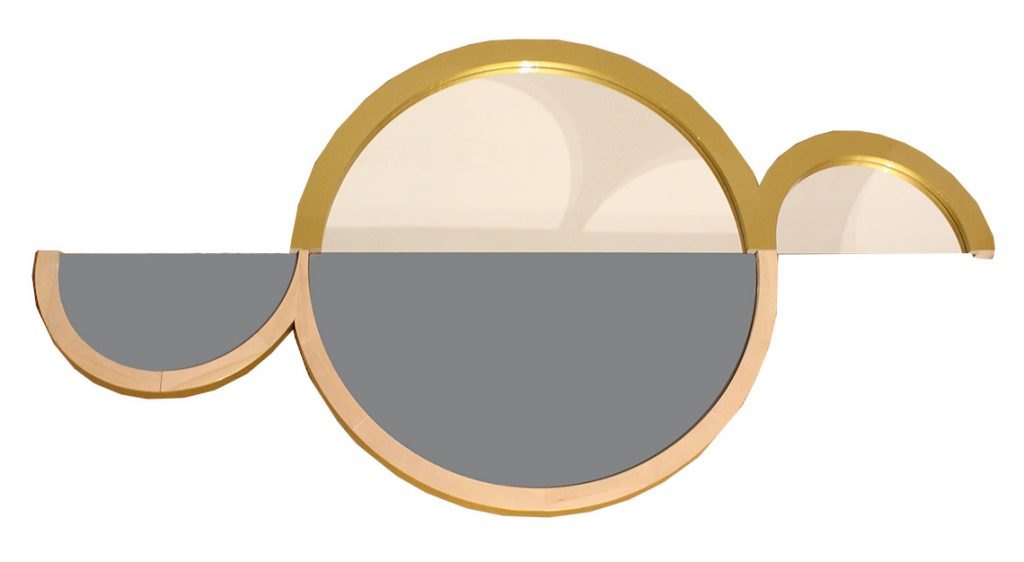

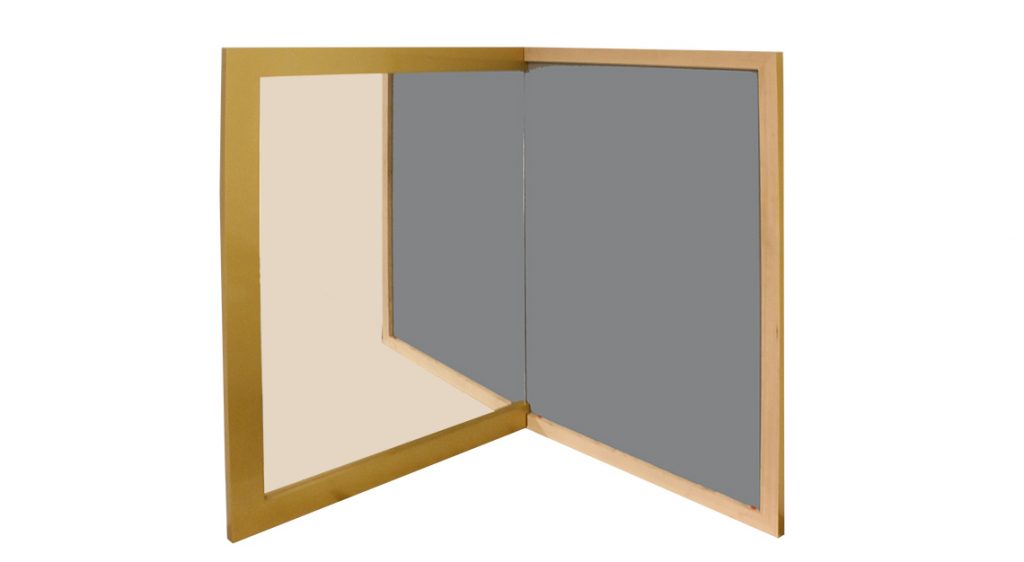

Pistoletto’s mother encouraged him to attend a school of “design and publicity”, at which he discovered modern art and realised the medium’s seemingly limitless possibilities for creation and invention. Freed from the trammels of naturalism or classical depiction, Pistoletto allowed his imagination free rein and describes his ‘eureka’ moment in 1961 with stunning, but not remotely surprisingly clarity.

The full story is available in the March 2019 edition of Robb Report Singapore; get the annual print subscription delivered to your doorstep or read on the go with a digital subscription.