Knowing how to detect cork taint or Brettanomyces can get a bad bottle replaced

Written by Jeff Jenssen, wine editor and Mike Desimone, freelance wine writer

While there is nothing more sublime than opening a highly anticipated bottle of wine and enjoying the liquid treasure within, there are few things more disappointing than finding out that a bottle you have purchased is simply undrinkable. If you have bought a bottle from a shop or at a restaurant and it is flawed, you can ask for a replacement, but it helps if you can explain what is wrong with the bottle. Just because you don’t like the wine or it is not what you expected is not a sufficient reason; there actually should be a problem with the wine in order to request an exchange.

Flaws are one of the reasons we look at wine in the glass and smell it before taking the first sip. Besides making a sensory imprint of the colour, clarity and aroma prior to drinking, these steps help us to detect any defects that may be present. That said, none of these conditions is harmful and there is no ill effect other than an unpleasant taste in your mouth.

Practice makes perfect and attending wine tastings can help to sharpen your nose and palate. If you are at a tasting and the host states that a bottle is flawed in some way, feel free to ask if you can smell it. This is a good way to improve your skills without being let down by a bottle you have spent money on. Meanwhile, here are five common wine flaws and how to identify them.

Cork taint

When a wine is described as corked, the culprit is something known as cork taint. Caused by a compound commonly called TCA or more formally known as 2,4,6-trichloroanisole, it suppresses the flavours in wine and causes a mouldy smell and off flavours. TCA primarily lives on cork, but it can also thrive on wood barrels and pallets in a winery, so it is possible (but highly improbable) that a wine bottled under screw cap could be affected by TCA. It is estimated that three per cent of wine bottled under cork is affected by TCA, so if you open bottles frequently there is a good chance you will come across several in the course of a year.

Master sommelier Dana Gaiser, fine wine manager for Domaine & Estates with Southern Glazers Wine and Spirits of New York, describes cork taint this way: “The primary aromatics one will find in a TCA-affected wine is wet, musty cardboard, while classic aromatics of the wine tend to be muted. On the palate, the fruit flavours tend to be muted and the finish will be shorter than typical of a clean wine.

Volatile acidity

Often called by its initials, VA, volatile acidity results when bacterial spoilage creates a large amount of acetic acid, a vinegar-like compound, in wine. This can happen if mouldy or rotted grapes make it through the sorting line, or if grapes come in contact with dirty surfaces during winemaking.

Mary Ewing-Mulligan, master of wine and president of International Wine Center, told Robb Report, “I used to find volatile acidity in wines much more often than I do now, because wines today are generally cleanly made. Many people encounter excessive VA as a smell, essentially the sharp smell of vinegar or nail polish remover. In my case, the finish of the wine confirms the flaw, when the acetic acid of the wine meets my throat in an unpleasant, sharp impression.”

Oxidation

Oxidation is the result of the natural air exchange through the cork in a closed bottle of wine, which happens gradually over time. It can also occur within hours or overnight in a bottle that has been opened and then stored unclosed or just re-capped with a cork rather than a device that would have prevented contact with air. This is likely to happen with wine that is poured by the glass in a restaurant.

Oxidation in a sealed wine is expected in older vintages, although wines that have been properly stored at cool temperature with controlled humidity will exhibit less of an effect. Some styles of wine such as sherry and madeira are purposely made in an oxidative style that gives them pleasant nut flavours. If you have ordered this style of wine or an old vintage, oxidised aromas and flavours are par for the course. Feel free to request a taste before committing to a pricey glass in a restaurant or wine bar, especially if you don’t see evidence of a wine preservation system on hand.

Kristin Mauritz, former beverage director at Del Frisco’s Grille in New York who now works in fine wine sales for Signature with Southern Glazers of New York, explained, “Oxidised wine shows aromas of fruit that has started going bad and gotten mushy and brown. On the palate all of the fruit notes lean towards those same browning notes. The wines also tend towards nutty, even toffee-like aroma and flavours. Oxidation also shows in the colour of the wine, with whites going from yellow to gold to even brown and reds going from red to orange or brown.”

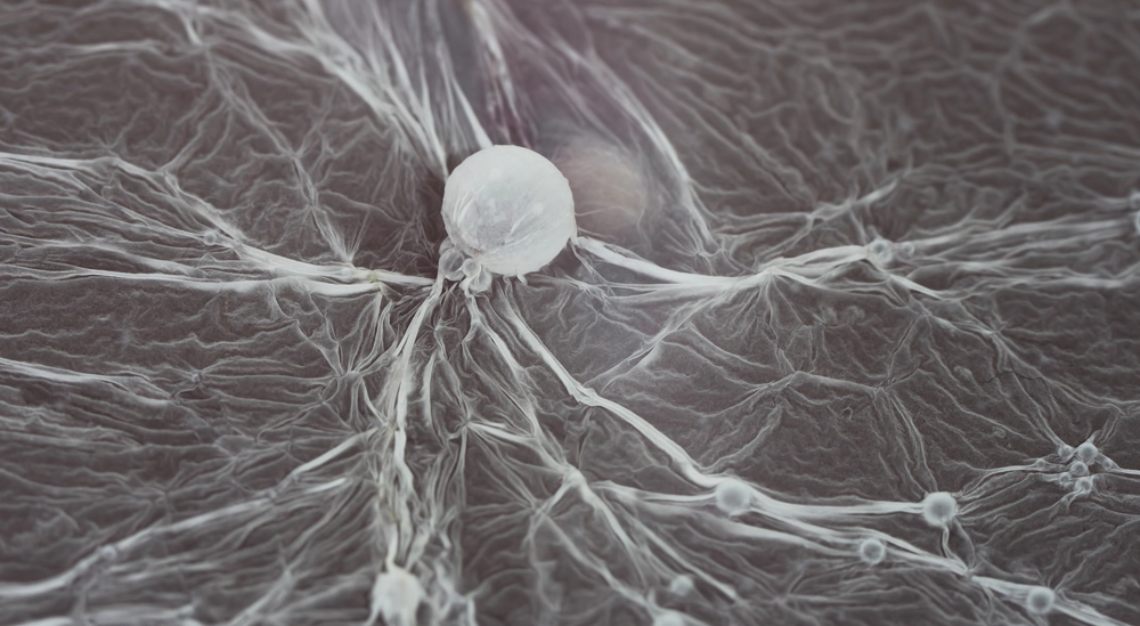

Brettanomyces

Often shortened to just “brett,” Brettanomyces is a type of yeast that can live in the air or on grapes themselves and grows all over wineries, including on barrels, walls and other surfaces. There is debate among wine experts as to whether brett is technically a flaw, as the odours and flavours it imparts to wine, especially in small amounts, are part of the desirable secondary characteristics that some wine lovers seek out. Some classic regions such as Bordeaux and Rioja are known for the leathery, earthy aromas and flavours of brett; its presence or absence is often the dividing line between “traditional” and “modern” producers in both regions.

Robin Kelley O’Connor, a sommelier and a familiar face at wine festivals and private events around the country, is the former Bordeaux trade liaison to the United States. He describes the effect of Brettanomyces as having “a mushroom-like, what I call ‘burnt offering’ smell, almost as if you had burnt bacon. But when it’s over the top, the smell can be overwhelmingly unpleasant—a foul, dirty dishrag smell. You can equate it to body odour.” One of the goals of a sommelier, O’Connor added, “Is to try to figure out your client’s tastes. If they are looking for a young, vibrant red they may not like an older Rioja or Bordeaux.” It’s important to know your own tastes as well and inquire as to whether a wine you are ordering may contain unpleasant levels of Brettanomyces, especially in an older bottle from a classic region.

Secondary fermentation

This is exactly what it sounds like; wine is made through the process of fermentation, and if it ferments again in the bottle, secondary fermentation has happened. In the case of sparkling wine, where secondary fermentation occurs under controlled conditions, this is an expected and desired outcome. However, if all the sugar has not been digested and converted to alcohol prior to bottling, unexpected additional fermentation can take place.

Heidi Turzyn, former wine director of Gotham Bar & Grill who is the co-owner of Beaupierre Wine & Spirits in New York City, recommends paying attention when the wine is opened: “You will see some fizz or hear the sound when opening still wine.” The next step to spotting secondary fermentation is the first step of wine tasting: Sight. Look at the wine in the glass, which should be clear and free of bubbles. Turzyn pointed out, “There are different intensities to bubbles when this re-fermentation occurs, but you will know if the wine has a small amount of clear bubbles.” The exception to this is in a natural wine, especially one made with low sulfites or none at all. This type of wine could be slightly cloudy and may also have a small amount of re-fermentation, which would cause a touch of effervescence. If this is the case, Turzyn recommends placing the wine in a decanter to allow the bubbles to dissipate and let any unpleasant odours blow off.

This article was first published on Robb Report USA