Rather than things of permanence lasting generations, they are typically torn down after a few decades and made anew. Here’s why

The cherry blossom famously represents the fleeting nature of human life, a beauty meant to be admired, enjoyed and let go. But in Japan, the brief, bittersweet cycle of death and rebirth also applies – surprisingly – to houses. This unusual national ideology ends up nurturing bold new designs and a growing slate of award-winning architects, as evidenced by the annual Pritzker Architecture Prize. Japan ties the US with more winners than any other country: eight in total, from Kenzo Tange in 1987 to Arata Isozaki in 2019.

The Western concept of a residence as a stable and secure long-term investment – more tree than flower – that will gradually increase in value over time directly opposes the Japanese view, which sees a house as a temporary structure that expires with its owner. A Japanese building is a short-lived consumer product, not so different from a car or an iPhone, that undergoes a period of fixed-term depreciation, set by the government at 22 years, after which it’s considered fit for the scrap heap. If an Englishman’s – or Westerner’s – home is his castle, a Japanese one is a worthless piece of single-use plastic.

The happy side effect of this throwaway ethos is that Japan has become a sandbox for architectural experimentation, a sort of deregulated enterprise zone that has incubated a culture in which some of the world’s most innovative and pioneering architects have thrived.

One of its most renowned, Kengo Kuma, the designer of the new National Stadium for the much-postponed 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games, tells Robb Report that the rapid turnover of housing stock gives young designers the opportunity to try new ideas. “In the Western world, architects design houses only for rich people,” he says. “But in Japan, most of the younger architects, their main field is to design inexpensive, small houses,” which gives them licence to experiment.

The path to this creative sandbox wends through influences both modern and ancient. The country still runs on a construction economy set up by the post-war government after Allied bombing destroyed many major cities. While a rapid building rate made sense for the fast-growing baby-boom generation, it has become excessive for a population that has been declining since 2011. In 2019, the number of new housing starts per person in Japan was around 1.8 times that of the US, despite an existing surplus of 8.5 million empty homes.

The vast majority of these new builds replace existing new-ish dwellings. The Japanese government dictates the useful life of a wooden house (by far the most common building material) to be 22 years, so it officially depreciates over that period according to a schedule set by the National Tax Agency. Even if buyers wanted to (which they don’t), they would struggle to purchase an older property as banks will not lend against a worthless asset. “The banks and real-estate agents cannot value the building beyond book value,” says Toshiko Kinoshita, a Tokyo architectural historian.

This odd set of incentives has roots in history and philosophy. Japanese property has long been destroyed by earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and tsunamis. In An Account of My Hut, one Japan’s most famous early texts, the 13th-century hermit Kamo no Chomei writes: “The bubbles that float in the pools, now vanishing, now forming, are not of long duration: so in the world are man and his dwellings.” So the “bubbles” of Japanese wooden structures – including the country’s most important shrine, in Ise, which succumbs to reconstruction from scratch every 20 years – were often rebuilt in accordance with Buddhist and Shinto precepts of transience. But after 1945, this embrace of the ephemeral hardened into concrete, says Kuma. “Before the war, people copied the traditional style, and that style was consistent,” he says. “But after the war… many styles and many sizes were mixed together and demolitions happened more often”, resulting in “real chaos”.

While construction itself accounts for only about six per cent of GDP, its influence spreads through a network of countless other dependent industries, explains Tokyo-based architect Riccardo Tossani. Japan is “a construction economy”, he says. “The whole economic and legislative infrastructure is organised around the demolition of existing stock and its replacement with new stock.” He names companies involved in demolition, building, concrete, steel and the electronic fittings that characterise every Japanese address. Other beneficiaries include “insurance companies and banks, whose valuations and lending structures reinforce the phenomenon of constant replacement”. Then come the property brokers, who rely on fees generated by such regular turnover, and, yes, architects.

Masahiro Harada, the co-founder of Mount Fuji Architects Studio and one of Japan’s most exciting young architects, according to Kuma, agrees that the Japanese concept of housing as an “ephemeral substance” and the dedication to “experimentalism” give the country’s designers an edge.

The result is a proliferation of weird and wonderful abodes, such as Harada’s Peninsula House on the eastern Japanese coast, an expanse of featureless concrete broken only by a vast, ziggurat-shaped slit of staircase on one side. Others have impossibly narrow proportions, or no apparent windows, or are entirely transparent. Kuma has described his 2005 Lotus House in rural eastern Japan as “basically composed of holes”. In Kinoshita’s view, “most of the crazy, photogenic houses can be a disaster for clients to live in comfortably”.

But the perverse beauty of the Japanese system means that all this doesn’t matter because your house never has to appeal to anyone except you. Not even your friends will likely see inside because entertaining chez soi isn’t part of Japanese culture. In the US or Europe, design gets constrained by the requirement to appeal to future buyers or pass the muster of neighborhood committees. In Japan, a future buyer will demolish your house, so you have nothing to lose. Sellers will often knock down their own house before putting their land on the market, to spare potential buyers the cost of demolition. Also, most buyers get only one shot because a home purchase is typically a once-in-a-lifetime event – usually facilitated via an extremely low-interest mortgage, thanks to a deflationary economy – so owners throw everything at it.

Gifted this incentivised clientele, Japanese architects are the envy of their global peers. “There are no design-review boards,” says Tossani, and “no requirement to have architecture judged by the community. The creative freedom is tremendous.” Neighbours never object to designs for “very unusual homes”, says Dana Buntrock, professor of architecture at University of California, Berkeley, because they are considered temporary structures. “The value of the adjacent houses is not affected because of built-in obsolescence. They do not last.”

On the flip side, an architect’s work will all disappear in short order. According to Zoe Ward, CEO of Japan Property Central, an upmarket brokerage, the process for a wealthy home buyer proceeds like this: “If you buy a 20-year-old house in Shoto (an expensive Tokyo enclave), it will have an old ’90s kitchen and bathrooms. You tear it down and bring in an architect to build a new house with a music room and a four-car garage. To get a starchitect, you have to be influential, but it’s easy to get small up-and-comers.”

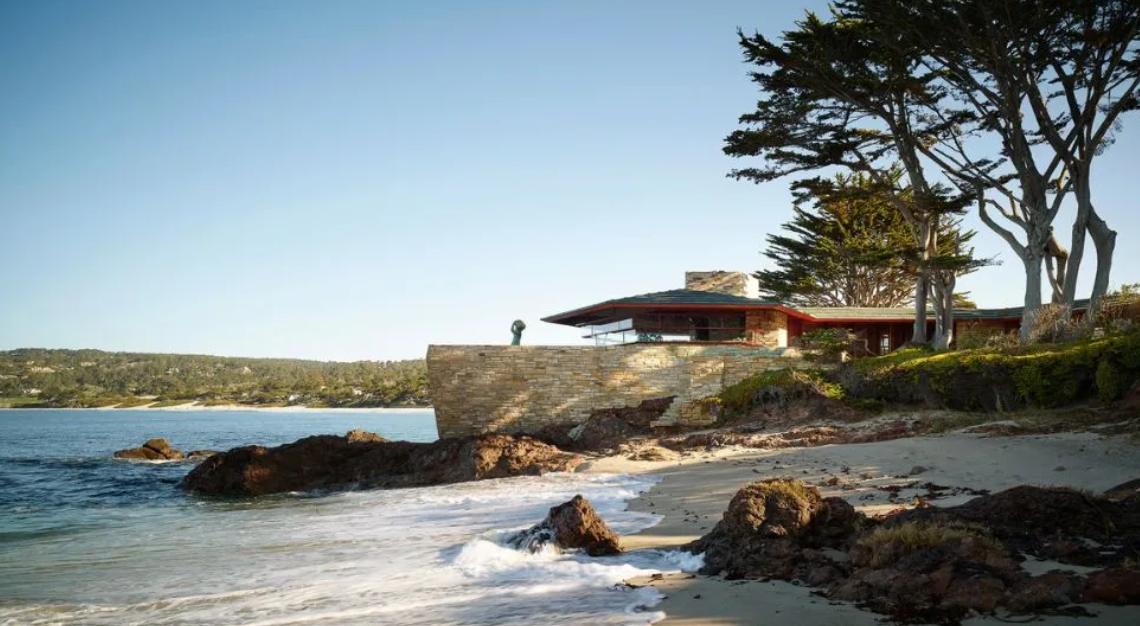

Japanese Pritzker winners are in demand overseas, too, from those who collect houses like art, says Buntrock. “You might get a beautiful home from someone like Jim Cutler or Bohlin Cywinski Jackson, but it doesn’t seem (so exciting),” she says. “But if you have a home by Kuma or Kazuyo Sejima (one of the two Pritzker winners for 2010), your friends understand the meaning of that cultural item – that you are being artistically adventurous, poetic, to a certain extent not concerned about conventional ideas.”

Back in Japan, a top architect’s name offers no protection against demolition. Even Frank Lloyd Wright’s Imperial Hotel in Tokyo lasted just 45 years. “A really unique place by a deceased architect with a fan base, you might find someone to buy and keep it,” says Ward. “But that’s a very, very small niche.”

Tossani feels slightly haunted by the fact that one of his projects, M Residence, sits on the former site of a home by Yoshio Taniguchi, best known for his 2004 redesign of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. “I felt a bit guilty because it was only maybe 20 years old, a pretty terrific house that was large and well designed, with an indoor pool,” he recalls. “But the clients insisted on demolishing it so they could have a house suited to their needs, and they had the money to do that.”

Others seem even less sanguine about the throwaway housing culture. The constant demolition is “illogical and a huge waste”, says Kinoshita, who’s a board member at Heritage Houses Trust, an organisation that campaigns to preserve architecturally significant residences. “I cannot understand why architecture lasts for as long as an electrical appliance.” Cause and effect become intertwined. If a house has a truncated valuable life, its builders can get away with shoddy construction practices, verging on built-in obsolescence, and its owners in turn possess little reason to invest in upkeep. This cycle of neglect hastens the death spiral and Japanese towns can appear run-down as a result. Signs of change burgeon, however.

“In recent years, there has been an unprecedented renovation boom in Japan, and buildings in cities like Kyoto have been renovated for residences, preserving the traditional image while bringing living spaces up to date,” says Masato Sekiya, whose small practice, Planet Creations, specialises in private homes. “This movement is progressing and such older buildings are maintaining their asset value.” Sekiya himself specialises in more experimental structures, such as Cliff House in Tenkawa, an eye-catching rectangular concrete prism suspended over a quiet rural river in Nara prefecture.

Japan ranks as one of the few countries in Asia where foreigners can buy freehold property without restriction, but overseas buyers have long been deterred by the country’s counterintuitive real-estate economics. This began to shift in 2013, after the devaluation of the yen made houses cheap. Kuma’s new luxury condominium project in central Tokyo, Kita, targets these investors, who firmly expect their real estate to hold its value at the very least. Westbank, the Canadian developer of Kita, which is also working with architects such as Bjarke Ingels, is trying to buck the depreciation trend by betting on the power of luxury (the penthouse comes with a rooftop infinity pool and a custom Rolls-Royce) and architectural stardust.

Paradoxically, change happens very slowly in Japan, and the national attachment to impermanence seems more or less permanent, as does the love of shiny new residences. “I cannot deny this is one of the reasons why we have so many globally successful architects in Japan,” says Kinoshita. “And I’m proud of it.”

The irony is that as soon as these architects reach acclaim, they tend to restrict their Japanese work to longer-lasting public buildings such as museums. Private homes become reserved for overseas clients, who see a value that endures.