The globally fêted Ghanaian-British architect has reached the upper stories of his profession, and his rule-breaking style is one reason why

A little more than a decade ago, David Adjaye hovered on the verge of bankruptcy, his budding architectural practicedevastated by the Great Recession. “Budgets were slashed,” he recalls. “I was employing about 30 people at that time and had about six decent projects, which was a lot for a young architect. But I was winging it. I wasn’t a businessperson. I lost all my savings, going through the insolvency system and paying off everyone personally.”

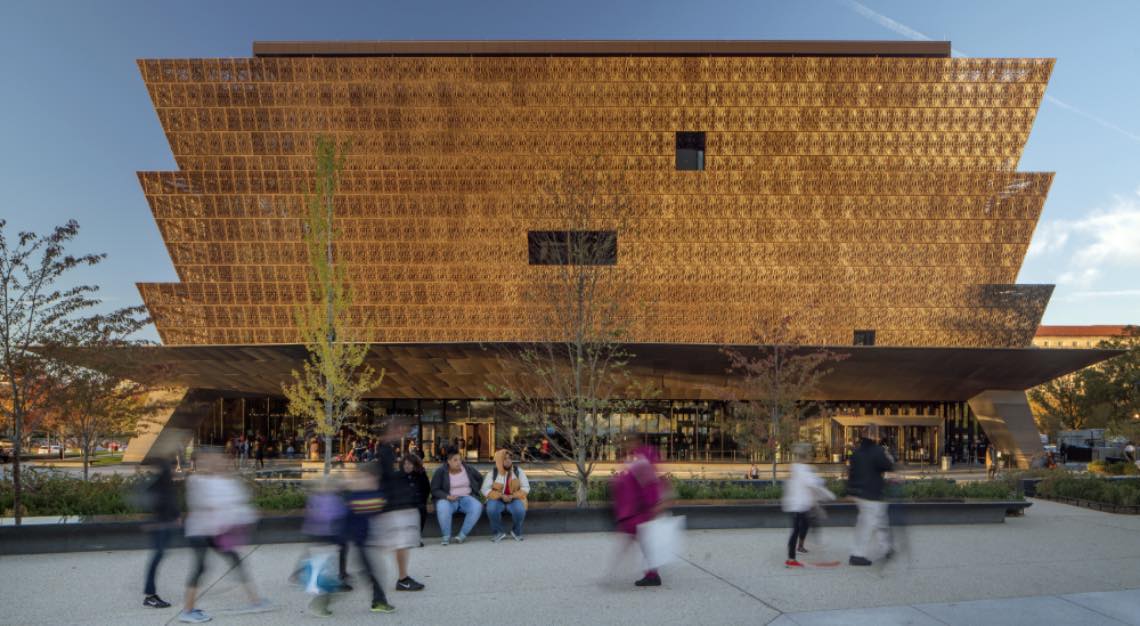

It was a rough comedown for an architect whose early works had gained notice for their rigorous and subversive designs. But only a year later, in 2009, Adjaye won the heated competition to design the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., marking a stunning reversal of his fortunes. “Just when people thought that I was done with,” he marvels, “the Smithsonian revived me and introduced me to America. It felt supernatural.” He describes the experience as a form of baptism.

As well as being a personal redemption, the museum, which opened in 2016, won the Ghanaian-British designer several awards and catapulted him into the starchitect stratosphere. The following year, thanks to a knighthood, he added “Sir” to his name. Adjaye stands among the most acclaimed architects working today and has become a go-to man for monuments and museums, including a planned Holocaust memorial by the Houses of Parliament in London. He has also become something of a spokesman for black architects, a role he inhabits eloquently, though reluctantly.

Sir David, 54, is now the very model of a modern celebrity architect, with homes and offices in London, New York and Ghana. He has designed houses for other creative luminaries – always a badge of honour – including Ewan McGregor, artists Chris Ofili and Jake Chapman, photographer Juergen Teller and Brad Pitt’s Make It Right Foundation, as well as for the late United Nations secretary-general Kofi Annan. Adjaye’s 130 William luxury condo tower is under construction in Lower Manhattan, and he is working with Four Seasons on its new private residences in Washington, D.C. The latest book to feature his work, David Adjaye: Works 1995 – 2007, will be published by Thames & Hudson this month.

He is not “wholly embraced” by the architectural profession, partly because he’s not easily classifiable, “not part of a gang”

Pre-pandemic, he spent much of his time at 9,144 m, between visiting professorships at Harvard, Princeton and Yale, and projects in Australia, Abu Dhabi, Lebanon, Norway, Senegal, Israel and Ghana. He sat at the top table with president Obama during a White House dinner for then prime minister David Cameron of the UK in 2012.

“He now has this amazing life of working in so many different places,” says Rowan Moore, architecture critic for The Observer newspaper in London. “I don’t know how he does it. It’s insane.” Adjaye’s popularity aside, Moore adds that he is not “wholly embraced” by the architectural profession, partly because he’s not easily classifiable, “not part of a gang.” Moore says his strength is “an ability to respond to a situation with something new. He’s good at the external wrappers of buildings.” His weakness, according to Moore, is that he’s “not a details man.”

In Britain, that kind of faint snootiness toward Adjaye is sometimes detectable amid the generally positive commentary, characterising him as a fashionable lightweight – a consummate networker and ambitious producer of novel, eye-catching projects popular with celebrities and the masses.

Sometimes this media caricature wears a bit thin. “Obama’s favourite architect,” as he was dubbed by the design press, was not, after all, awarded the commission to design the presidential library in Chicago (that went to Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects). He did not grow up in wealthy Hampstead, as is regularly reported by the press on both sides of the pond, but in the decidedly unglamorous nearby suburb of Cricklewood.

In person, Adjaye is more cerebral and vulnerable than his media persona suggests. It’s clear that he cares much more about his public works than any ritzy condo tower. “I’m attracted to projects that have transformational qualities and justice qualities,” he says. “That’s what turns me on.”

“I’m attracted to projects that have transformational qualities and justice qualities. That’s what turns me on.”

He speaks to Robb Report via Zoom from Accra, his carefully modulated statements sweetened by an infectious giggle, his grey office backdrop enlivened by a brightly patterned yellow shirt, though he chooses a more somber palette for Robb Report’s photo shoot. His African practice has been booming, and he’s spending the pandemic in the Ghanaian capital with his wife, Ashley Shaw-Scott Adjaye, and two young children, toying with ideas for a new family home there.

Adjaye had a peripatetic expat childhood. The son of a Ghanaian diplomat, he lived in Tanzania, Uganda, Kenya, Ghana, Egypt, Lebanon and Saudi Arabia before the age of 13, when the family settled in London. His “unrooted” youth, as he calls it, was further disrupted by trauma when one of his two younger brothers, Emmanuel, contracted an infection as a toddler that left him mentally and physically disabled.

Adjaye’s mother, Cecilia, became Emmanuel’s caregiver; he still lives with her in London. His father, Affram, took a demotion to move the family there to get the best care for the child. “It changed the dynamics of the family,” Adjaye says quietly, “because essentially, you know, this one-year-old boy suddenly became the only focus that my parents wanted to deal with.”

Thrown into a London state school after a childhood spent at private international schools, the teenage Adjaye “got into a lot of trouble,” as he puts it. He found the English school “shockingly provincial.” In retrospect, however, he values his itinerant upbringing. “The best education is an education you don’t realize you’re being given,” he says. “You’re not frightened by new situations.” He still feels at home when traveling. “I’m most comfortable working in every part of the world that I am allowed to go,” he says, grinning.

Lesley Lokko, dean of the Spitzer School of Architecture at the City College of New York and a fellow Ghanaian Brit who has known Adjaye for about 20 years, attributes his success to having grown up as “the consummate outsider.” Adjaye has, she says, “always been half in and half out of situations. That gives you an antenna. He is incredibly sensitive to contexts.”

This insight into context, according to Lokko, is the key to understanding a trait of Adjaye’s that bothers architectural critics: “He has no signature style, except that whatever he comes up with will be deeply thoughtful.” She adds that “his vision is large scale, and so he’s not somebody who obsesses over the micro-details of projects.”

Moore characterises him as “an architectural diplomat – charming and persuasive in person and in his most successful buildings. He is able to move between different milieus and communicate across them. Whether it’s the East End of London or [Washington’s National] Mall or Ghana, there is an equal level of respect.”

Adjaye remained uninspired by school, despite his parents’ efforts.

Success was not a foregone conclusion. Adjaye remained uninspired by school, despite his parents’ efforts. “They were typical West African,” he says. “My father was hell-bent on education.” To enter a profession was the way to “escape all the ills of the world. That was drummed into us.” Yet Adjaye persuaded his father to let him go to art school, a concession he still feels grateful for. “That’s when I fell in love with my dad again.” (Another brother, Peter, became a conceptual sound artist.) Adjaye’s principal concern when his business went bust in 2008 was that he would embarrass his father.

After art school, he went on to study architecture, earning a master’s at the Royal College of Art in London, where he became friends with many of the Young British Artists promoted by Charles Saatchi in the 1990s. His student design for an inner-city respite centre for disabled children (inspired by his brother) won a prestigious national award from the Royal Institute of British Architects. The same body recently named him the 2021 recipient of the Royal Gold Medal, one of the world’s most prestigious architectural awards.

During his studies, Adjaye spent a year in Japan, at the Kyoto University of the Arts, an experience he describes as “a profound time, probably the most important time in my education.” Ultimately, it led him to a new appreciation of African aesthetics and the beginnings of what he now calls his “obsession” with helping African countries develop architecturally.

Japanese reverence for the simplicity of their indigenous buildings, and the way they elevate plain, natural materials to an art form, struck him as applicable to African huts. “It made me start to look at Africa again, not as a place that was undeveloped and weak but as a place of immense aesthetic potential,” he says. “I would go into a teahouse and I would think, This is like a hut. It’s basically thatch and a bit of timber and mud. So why is my grandfather’s village not special but this is? It was like seeing two different worlds, where one was revered and the other was despised. It was a revelation.”

Back home, after college, Adjaye struggled to get work in a profession that is notoriously hard to break into without connections.

“Architecture is like the art world in the sense that it needs another artist to anoint an artist,” he says. “Artists don’t just emerge on their own. Architecture is the same. It requires patronage.” He believed that his race marked him as an outsider. “I felt like a misfit. I spent my entire time trying to fit in, reading as much as I could about European architecture.”

“Artists don’t just emerge on their own. Architecture is the same. It requires patronage.”

Adjaye spent a few years scraping by, building sets for music videos, and then his friend Chris Ofili, a painter who had just been propelled into stardom by Saatchi, asked him to design a studio. That led to a commission in 1999 from an artist couple for what became Elektra House in East London. The house, inspired by the Japanese practice of putting all the windows in the back to maximise privacy, garden views and light, had no windows onto the street – just panels of inexpensive, plain, dark-brown phenolic plywood – and a rear façade almost entirely of glass. “They let me do what I wanted, within the limits of their money, which was nothing. And it made the cover of the RIBA Journal,” Adjaye says.

In Britain, with its devotion to bay windows, his concept was seen as radical. “Suddenly it was like, who is this black kid building very weird buildings?” Adjaye says with a giggle. Elektra House attracted the attention of Richard Rogers, the Pritzker-winning modernist architect, who has been his friend ever since.

The house still exemplifies Adjaye’s creative method. He first compiles “a body of knowledge and research and context” on the local area, he says, then considers how to use form and structure to express the building’s purpose within that framework. “I’m always reading the context and trying to better the context,” he says. “That’s my first trick.”

The point of contextualizing is not to fit in but to subvert. “Architecture is about politics with a big ‘P’,” he says. The aim is to change “the way in which people perceive buildings in that area” and to entice them “to aspire to something better. How does a building do that? Just very simple things like not having walls or being completely accessible.” Once the idea is clear, “the building self-generates,” he says. “All questions about what kind of windows or energy systems [to use] are answered through that initial lens.”

For example, in Elektra House, the brief was to capture light. “So I thought, I’m going to make a house that tracks the sun, not deals with the street,” he recalls. “And so the house is blank but absolutely full of light. People said, ‘This is not a house.’ It’s not a house that’s about the street and windows. It’s a house that’s about the world and light. It’s really about having a different perspective.”

Elektra House made Adjaye’s name, but it was almost his undoing. The local authority took him to court for breaking planning laws (that windowless façade), and Adjaye says he was saved from a possible criminal conviction only by the intervention of Rogers. The head of the local governing body was so impressed that he invited Adjaye to enter a competition to design a neighbourhood library, which, naturally, he won.

That foray into public infrastructure led to a pipeline of civic works, beginning with the Nobel Peace Centre in Oslo in 2002 and culminating with the Smithsonian. He was invited to enter the competition for the Mall’s latest museum on the basis, he says, of his recently completed Museum of Contemporary Art Denver and his design for a vast business school in Moscow.

Asked why the Smithsonian invited him to compete, he says, “There are lots of African-American architects, but none had an international profile, and I emerged as someone who had worked in the US and Europe. I was the first black architect that they’d seen operating continentally.”

Worried that his threadbare practice was too small to take on such a challenge, Adjaye teamed up with Philip Freelon and J. Max Bond Jr., two well-established African-American architects. Their winning bid beat out such A-list names as I. M. Pei, Norman Foster and Diller Scofidio + Renfro. (Bond died in 2009, but his company carried on the project; Freelon died last year.) The resulting triple-tiered building, designed to resemble a West African crown, is clad in glowing bronze-colored aluminum panels perforated with delicate lattice patterns, which vary in color with the changing light.

Alexandra Lange, a design critic and author, describes the panels as “a great calling card.” Adjaye, she says, “understands pattern and intricacy in a way that a lot of contemporary architects don’t. I was really blown away by how well his choices fit in while also making a distinctive museum. It needed to hold up to the neoclassical marble buildings, and he picked a great way to do that.”

She links this approach to Adjaye’s design for the Sugar Hill affordable-housing complex in Harlem, completed the year before the Smithsonian, where the stark gray concrete exterior walls are etched with an ornamental rose pattern. The effect was dismissed by New York magazine as “crude, the product of an evening spent fiddling with Photoshop,” but Lange sees it as “a beautiful pattern,” evidence of Adjaye’s sensitivity to material. “Concrete, metal, mirrors and glass – each has its own beauty and quality,” she says. His exteriors are “like a carapace – one thing is happening on the outside and something different on the inside.”

Adjaye is now on speed dial for prestigious government commissions, including a master plan, with other firms, for a new Parisian quarter close to the Bibliothèque Nationale de France François-Mitterrand and the reconstruction of Haiti’s National Palace. In the US he is designing the Princeton University Art Museum, and his new home for the Studio Museum in Harlem is under construction. His blueprint acts “as an extension of the very spirit of our Harlem community,” says the museum’s director, Thelma Golden. Adjaye has drawn on the surrounding architectural vernacular for inspiration while reframing it in an unexpected way that makes the museum more welcoming to the public. “He re-envisioned the soaring sanctuaries of Harlem’s churches as the museum’s top-lit atrium,” says Golden, while local brownstone stoops “became tiers of wide steps leading down from the entrance to the program space, with each step doubling as a place where the audience can sit.”

With global success has come racial role-model status, a responsibility Moore says has been “partly put upon him by the architectural profession being so damn white.”

Adjaye’s main focus now is Africa, and he’s working on a new campus for the Africa Institute, a research centre in the United Arab Emirates that specializes in the study of Africa and its diaspora. He describes his current residence in Ghana as a “third chapter,” after his early work in London and a second, Smithsonian-focused phase in the US. He says he feels he’s “being summoned to deliver for a country. We are now working on the National Cathedral for Ghana and, as a result, in West, East and South Africa. This seems to be a very powerful new time.”

With global success has come racial role-model status, a responsibility Moore says has been “partly put upon him by the architectural profession being so damn white.” Adjaye finds this labelling reductive and somewhat patronising. He recounts how, “when this whole Black Lives Matter thing happened, the number of magazines that called me to ask, ‘Can you just say what it’s like to be a black architect?’ I refused most of the time because I don’t feel like it’s my job to educate [people on] that issue anymore.”

But he also acknowledges that his pioneering accomplishments have profound personal meaning. “It’s not a burden. I’m very proud, so proud of the Smithsonian,” he says. “I feel so thankful. Now when I look at my children, I feel like there’s something in the world that speaks to them.”

His fame is also genuinely inspirational to young black creative professionals. “He’s a complicated figure partly because there’s no precedent for someone like him,” says Lokko. “He resists the label of the black architect, and yet it’s the elephant in the room whenever anyone considers his work. He’s very clear about being British African, and his references come from a deep understanding of the African continent. People don’t always know how to read that.” Lokko once brought Adjaye to lecture in Johannesburg, where she was teaching at the time. “It was like the second coming of the Messiah,” she recalls. “He is incredibly meaningful for the students.”

On the role of race in national historical and political narratives, Adjaye’s views are nuanced. He opposes the removal of controversial statues. Taking them down, he explains, warps history. Erasing the memory of problematic historical figures “creates all the confusion that we’re now experiencing in the 21st century with Holocaust denial and people not understanding American history,” he says. Their continued presence, on the other hand, “activate[s] questions,” he says, and helps prevent our forgetting – and repeating – history.

In the same way, he believes Britain needs to stop treating its former empire as a taboo topic and instead engage with its real history, perhaps by way of a museum. “Most Brits only understand the end bit, the froth of empire,” he says. “To navigate in the world in the 21st century,” Britain needs to “understand its own evolution . . . the good and bad,” he reflects. “I think that a great nation says, ‘Let’s try to resolve it,’ not ‘Don’t talk about it.’”

The purpose of memorials, and the process by which nations decide what and how to commemorate, are among his favorite subjects for reflection. Traditionally, monuments enable closure, Adjaye says. “You’re supposed to reflect on immortality and that [the dead are] in a good place. So you make it out of marble and you make it feel eternal, so it feels like it’s sorted, it’s done, and you’re allowed to forget.” His own memorial buildings, in contrast, are “trying to create questioning and thinking.”

He reveres Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the National Mall because its immense list of the dead and missing does not try to edit history into a hierarchical narrative. No single name or rank matters more than any other. The experience of that long walk, reading the names etched into the wall, can be seen in the physical journeys that he created in the Smithsonian and his plans for London’s Holocaust memorial.

Both immerse visitors in uneasy darkness before drawing them out into the light. The proposed Holocaust memorial – which is mired in planning disputes – will force each visitor, including children, to pass through a bronze-lined chamber alone. “It’s a little window into what the Holocaust did to millions of people,” says Adjaye. “In all the surveys, 20 per cent of English people think the Holocaust didn’t happen. We’re using architecture to reenact empathy within people, empathy towards the subject. Not [to create] the sense that it’s finished, but the sense of, oh, my God, I really need to pay attention.”

From his house in Africa, Adjaye muses on human history and how its stories can take physical form. How do we create an honest account of the past to teach our children? How do we guard against the erasure of unpleasant history and the risk of repeating our mistakes? How do we empathize with excluded groups? His mission is a hopeful one: the knitting together of humanity and of the present and the past.

As for the future, he’s bullish on cities, post-pandemic, pointing to the improvements in sanitation after tuberculosis epidemics and in building safety after 9/11. He envisions “more breathable buildings, more varied ecologies” and improved access to sunlight. “The good thing about human beings is that we are good at evolving,” he says. “Once we see the problem, we evolve past it and deal with it. It will make the density which we can’t escape better. We’re going to build bigger buildings. We’re going to make bigger and better cities,” he grins. “It’s coming. It’s already here.”

This was first published on Robb Report US