From a musical weapon of choice for rebellious youths to collectibles that shake up the art world

Jens Ritter has made electric guitars for the likes of George Benson, Nile Rodgers and Prince to play on and enthral music fans from across the world. But for his latest act, Ritter has opted to work with silence instead.

Sparked by a rude awakening when he first heard—and unwittingly enjoyed—music created by artificial intelligence, Ritter started to ruminate on the demise of human creativity. This led the 51-year-old luthier to produce a series of defiant, one-off electric guitars. Christened The Sleeping Beauties, the guitars are made in a way that they will not be played for the next 100 years. Save for a brief moment when Ritter tuned these lavishly handcrafted and decorated instruments, their electronic components have since been deactivated. The guitars are sealed in bespoke humidors inscribed with their respective ‘wakeup dates’.

“The electric guitar is a significant object in the development of human culture. Because it could be amplified, for the first time in history, it allowed a musician to reach out to thousands of people at a time,” says Ritter. “The Sleeping Beauties is like a time capsule. People can pass on wealth or real estate, but this is a piece of art that symbolises life and culture that future generations can inherit.”

If such artsy elevation of rock and roll’s most democratic instrument sounds rather grandiose, it is only because Ritter has earned the right to be indulgent. An open-secret among the music fraternity since the early 2000s, his works are collected by major museums such as the National Museum of American History in Washington DC, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Earlier this year, Ritter staged his most recent solo exhibition, Rock ‘n’ Roll Masterpieces, in Los Angeles, which showcased The Sleeping Beauties, alongside seven other collectible guitars, one of which had been bought by Lady Gaga.

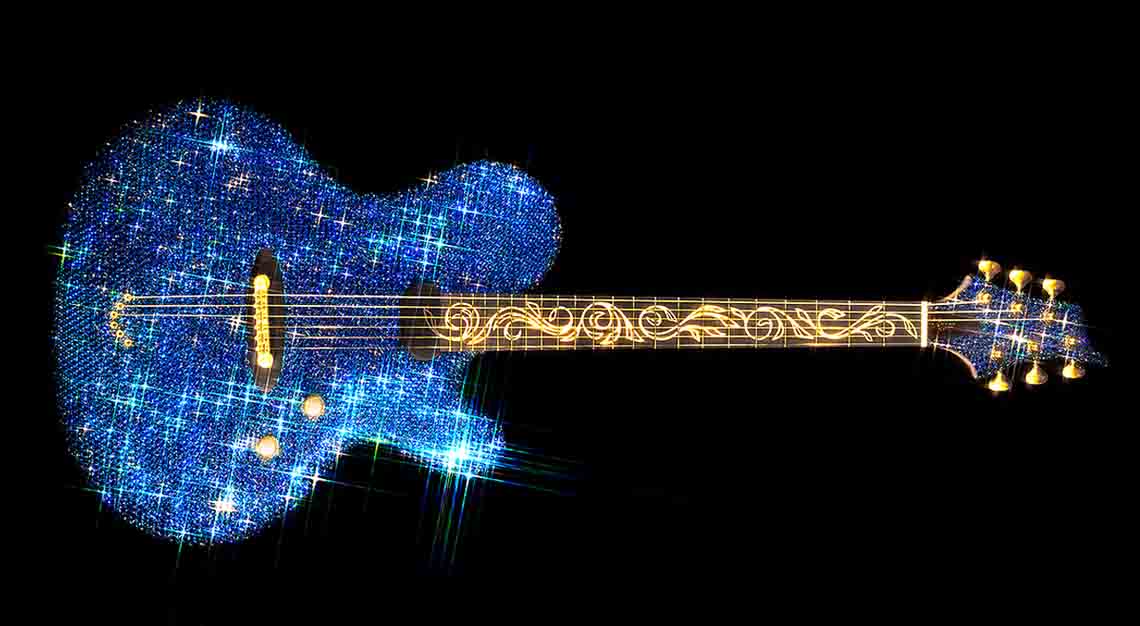

Ritter first got on the radar of art collectors in 2008 when he created what was then the world’s most expensive bass guitar. Called Royal Flora Aurum, the instrument was valued at approximately US$250,000 and featured a rare maple wood body, a nut carved from 10,000-year-old Siberian mammoth-tusk ivory, diamond-festooned gold knobs, and a fingerboard with gold floral inlay.

Royal Flora Aurum was commissioned by a client, who simply asked that Ritter “go crazy” to create the one-of-a-kind instrument. While he fondly recalls the experience, Ritter says that he has since moved on. “If you can make a great guitar, you are a great craftsman. But this has nothing to do with art. Art is about creating something new: communicating ideas, communicating psychological content.”

From craft to art

Ritter still works out of the workshop where he first started, in a small town at the southwestern part of Germany called Deidesheim. His modus operandi, however, has evolved. “In the beginning, I was totally focused on function. I wanted to make guitars with the best playability and tone. I still have meetings with my team on such matters, but the foundation is already there. Now, I am more interested in the psychology of the instrument.”

It was American contemporary artist, Jeff Koons, who helped Ritter flick the switch. Koons told him, in no uncertain terms, to stop thinking about being an artist and start becoming one instead. Coupled with the fact that, by Ritter’s own admission, he has become financially robust over the years, he was ready to embrace his evolution from craftsman to artist.

“In the past, if say, I wanted to make a green guitar, but a customer wanted a red one, I would make the red guitar,” he says. “I needed to pay the bills but that was killing my art. When I decided not to do that anymore and refused projects that didn’t align with my artistic vision, my clients were shocked at first. However, art collectors sensed that I was being true to myself, and that was important.”

Regardless of artistic inclinations, Ritter’s instruments are instantly recognisable. Crafted from high quality hardwood, the guitars feature sensuous silhouettes and are finished with precious ornamentations ranging from gem-encrusted inlays to gold electronics. Specialist magazines have gushed over Ritter’s Stradivarius like techniques that amalgamate high-tech materials and modern design with traditional craftsmanship, as well as the instruments’ playability and exceptional tone.

To Ritter, however, these are basic virtues to be expected in his creations. Instead, artistic quality and expression are what elevate his instruments. To illustrate, he cites two of the Sleeping Beauties models. The Alcudia Bay 2.0, for instance, with a maple body sheathed in iridescent turquoise, recalls the look of the pristine waters surrounding the Majorca Islands where Ritter and his family spent a recent vacation. (“The happiest time of my life,” he reminisces.) There is also a bespoke Sleeping Beauty for a collector and devoted fan of The Beatles. The guitar is incorporated with the actual tarmac from the iconic zebra crossing in front of Abbey Road Studios where The Beatles famously recorded.

Ritter says most of the collectors of his guitars hardly play the instrument, but it doesn’t bother him. He reckons that they value the conceptual thinking that goes into creating the instruments.

“From an artist’s perspective, I see my guitars as a tool to communicate my ideas, my anger and my emotions to the world. One guitar may sound the same as another, but when you put art and feelings into it, the energy of the instrument is totally unique and different,” he says.

This story first appeared in the July 2023 issue. Purchase it as a print or digital copy, or consider subscribing to us here