The capital’s bespoke tailoring scene is in rude health, thanks to a new breed of young entrepreneurs who have left fashion’s most famous address to set up on their own

A Savile Row suit is a beautiful commodity: It’s also a deeply traditional one. The Row’s largest bespoke tailors—those, such as Huntsman and Henry Poole, whose names are spoken reverently by connoisseurs—stick rigidly to their house styles and offer an experience that can at times be, if not always intimidating, then perhaps not entirely a bundle of laughs, either.

And while men’s style has grown more casual in recent years, many of the senior denizens of The Row have continued to prioritise formalwear and business suits rather than evolve with the times. It’s a state of affairs that can be frustrating to younger tailors, particularly those who joined the industry with dreams of working on the most famous street in fashion but who are also desperate to remain relevant, both culturally and sartorially.

Kimberley Lawton (above), who left Savile Row behind to launch her own tailoring business in 2018, refers to these young professionals as “people who wanted to be more creative and not make navy and green tweed all the time.” And she’s not alone. Now, thanks to Lawton and a group of similar entrepreneurs, you no longer need to step inside the mullioned shopfronts of Savile Row to get creative with some of the best bespoke tailors in London.

A number of independents, operating in characterful ateliers in cool parts of town, are offering clients a more personable, creative partnership than many long-standing bastions of trad British tailoring. And whether they make dramatic C-suite suiting, low-key “lunch suits” or casual suede jackets, this up-and-coming generation have transformed the British capital’s tailoring scene from a single, siloed street into a vibrant “studio city.” Here are five of the best.

Taillour

Picture, in your mind’s eye, a typical bespoke tailoring house. It won’t look—or indeed feel—like the one created by Lee Rekert, 48, and Fred Nieddu, 36 (left to right, above), who’ve set up shop in a trio of redbrick Victorian studios in East London. From the whitewashed walls covered in contemporary art, some drawn by a local tattoo artist, to the potted plants and colourful half-finished jackets hanging on pegs, the space is fundamentally fresh and inviting. Rekert and Nieddu meet with clients in one studio, while the others house the cutting and making rooms where a small team bring Taillour’s clothes to life.

The brand’s Francophile name is a telling mark of distinction, too. The word “taillour” is Old French for “one who makes clothes,” and that’s how Rekert and Nieddu see themselves: no more, no less. “It’s about making really lovely products for really nice people, which they’re comfortable in,” Rekert explains.

“We take heritage or vintage [designs] and passion for craft and make it relevant,” Rekert adds. The result is a garment—whether a crisp fresco suit or slouchy cashmere sport coat—that looks modern and trim but feels very easy to wear.

They’re not short of commissions. Quite apart from a burgeoning client list (as well as servicing European customers, the pair host trunk shows in New York six or seven times a year and are expanding to other US cities), Taillour also produces costumes for high-profile TV and film projects. Nieddu has created the menswear for every season of Netflix’s The Crown and dressed Ralph Fiennes’s “M” in the Daniel Craig–era Bond franchise. Future film projects include the forthcoming Indiana Jones movie and Roald Dahl prequel Wonka, with Timothée Chalamet.

These on-screen creations have ranged from conventional suits with exacting period details to ’80s-style one-piece ski suits in technical fabrics and suede safari jackets (now a Taillour signature after Nieddu made one for The Crown to rave reviews). A big part of their job, they say, is “exploring new ideas and new ways of doing things.” And it’s that can-do approach, combined with exemplary quality, that makes what Taillour produces so exciting.

Ollie’s

Oliver Cross is larger than life—in more ways than one. The closest London has to a 37-year-old Viking in a tweed sport coat, he’s warm-hearted and lively. His studio, an industrial-chic concrete space beneath London’s Oxo Tower, is full of personality. Cross has filled it with midcentury furniture and projects classic movies onto the wall above the cutting table while he works (that’s when he’s not blasting out his vinyl collection).

A visit here typically starts with a man-hug, a beer and a half-hour chat about life. “A cutter once told me to always keep customers at arm’s length,” he says. “I’ve always thought, ‘Bollocks to that.’ I want to create a community of friends who come and see me.” Ollie’s is a relatively new venture—Cross set up the business in December 2021—but in that short time he has already built a healthy list of clients who are drawn to his relaxed approach to tailoring.

Cross was a late bloomer. He decided to pursue a passion for clothes following years spent working in financial services and only embarked on his tailoring career at 27. Following a lucky break with Meyer & Mortimer, he joined now-defunct tailor Benson & Clegg as a cutter but struggled with what he perceived to be the house’s stuffiness. When the company entered administration in November 2021, Cross struck out on his own.

He tends to cut a “West End style” jacket with some structure in the chest and shoulders but is only too happy to experiment with different constructions and silhouettes. Spend time with him and you soon realise that he revels in technical tailoring minutiae. It’s not unusual to take 20 minutes of a fitting to decide on the angle of the lapel or the amount of roll in your sleeve heads. It all adds to the experience—and enhances the impression that you’re in the safest of hands.

“There isn’t an Ollie’s look,” Cross explains. “I think the harder part is understanding the individual. When they’re stood in front of that mirror, you know there are certain little nuances that you might want to take away from a garment or add to it, in order to reflect their personality as an individual.” To do this, he cuts key elements of his patterns, such as the jacket’s front edges and lapels, using what tailors call “rock of eye” or “freehand.” Normally pattern cutters will use templates to shape lapels, but Cross prefers to draft by instinct.

“I’m not that business-minded,” he adds. “All I’ve ever wanted to be is myself and just to be comfortable in my working environment. You can only get the best out of somebody if that’s there.”

Lawton

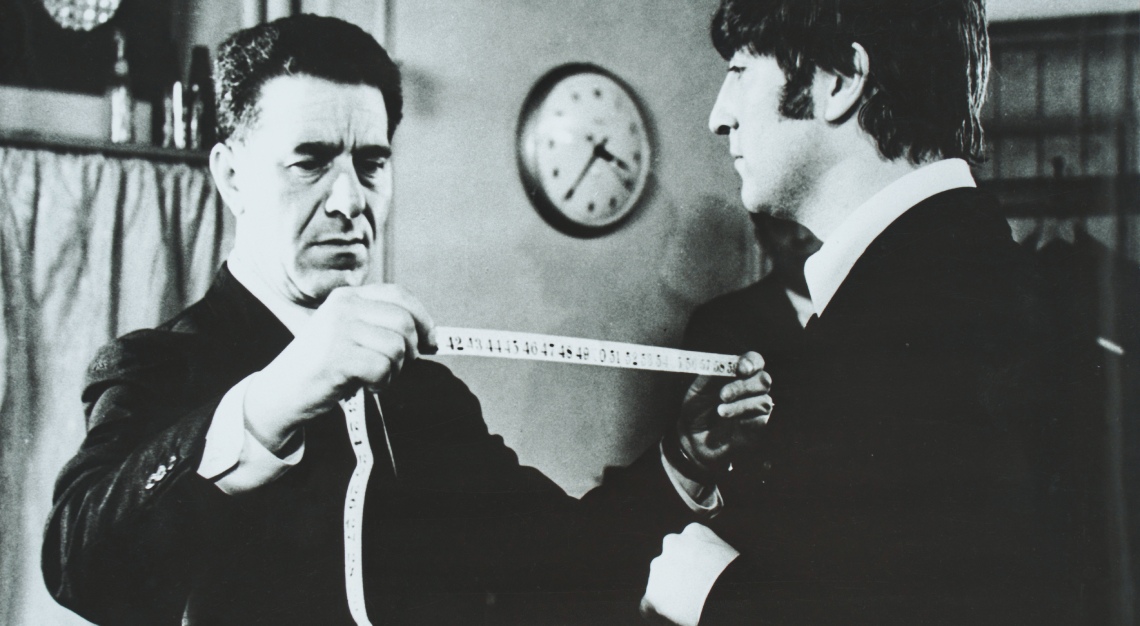

Back in the 1970s, famous Savile Row tailor Tommy Nutter—who, along with his business partner, Edward Sexton, dressed every superstar of the era from the Beatles to Elton John—was nicknamed the “Rebel on the Row.” Today, 28-year-old Kimberley Lawton is perhaps best thought of as the rebel off it. Her clothes are technically innovative and aesthetically striking: Think bold double-breasted chalk-stripe jackets with sweeping lapels and wide-legged bootcut trousers finished with thick cuffs.

“I want to make garments that make people feel like they’re wearing something that gives them the confidence to strut down the street and turn heads,” she says. “I really get a kick when my customer says, ‘Oh, I was sat being grilled by one of my clients, and all I could think was well, I look better than you.’ ”

Her house style, informed by her love of 1970s and ’80s rock (she references Bowie, Blondie and Mick Jagger as influences), is fittingly striking: Structured shoulders, roped sleeve heads and a slim waist combine to create suits that nod to Nutter’s retro designs without being copycats. To accentuate these dramatic proportions, Lawton also inserts a horizontal band of horsehair canvas into the skirts of her jackets: This sits around the wearer’s hips and helps to induce a defined, hourglass silhouette—a technical innovation that’s rooted in couture womenswear.

Indeed, unsurprisingly, Lawton has a reputation for making exceptional suits for women. “I was so irritated growing up, trying to find any clothing—especially tailored garments—that made me feel powerful,” she explains. “When I make something for a woman, they stand better and feel confident. I love to give that to my clients and see how they just feel sexy.” Key to achieving this, Lawton adds, is her understanding of both male and female body types: “It’s not a man’s suit cut for a woman—it’s a woman’s suit with masculine elements.”

Despite her relative youth, Lawton has plenty of both experience and ambition. She studied at the London College of Fashion and worked as an under-cutter at Huntsman before launching Dobrik & Lawton in April of 2018 with a colleague she met on The Row. Dobrik subsequently left the business to pursue other projects, and Lawton relaunched as sole owner in September 2021.

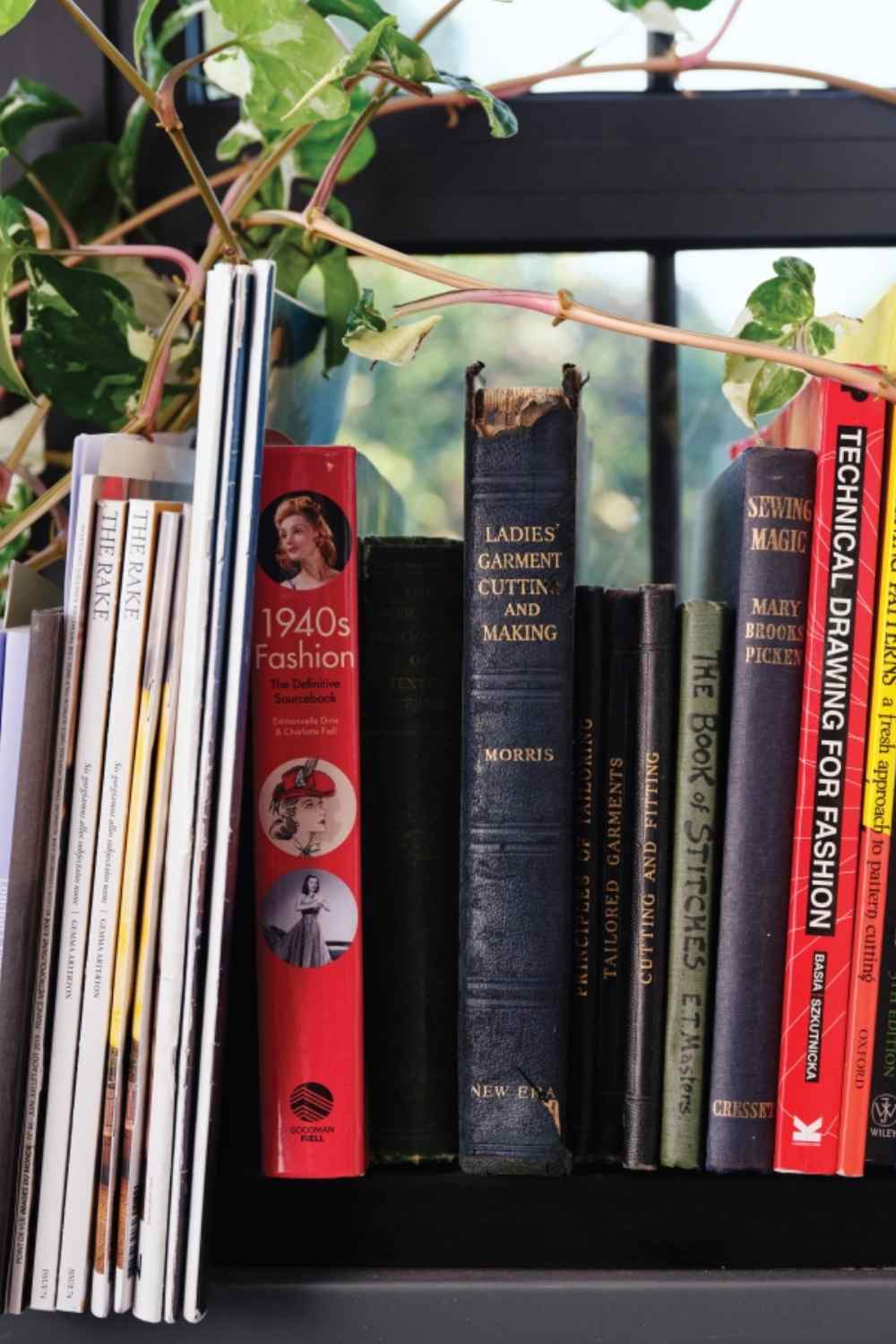

She cut and assembled 29 suits between January and October 2022—a remarkable achievement for a young tailor flying solo. Currently she works out of a small studio in northeast London, with black-painted walls and shelves overflowing with fabric samples. She travels into central London to meet clients at their homes, hotels or offices but has expansion plans in the offing, space-wise. “I think the next goal would be [to make] 60 suits a year,” Lawton says, “to be able to have a store somewhere and then just keep growing from there.”

Atelier Arena

Tom Arena doesn’t hang about. He has been self-employed for just over a year (he opened in St. James’s in September 2021) and has already dressed actors including Gary Oldman, Stephen Graham, Connor Swindells and Jack Lowden. At 45, he’s among the eldest of the new wave of independent tailors, but his attitude toward men’s style is distinctly youthful. “You need a bit of flamboyance, a bit of character in the garments,” he says. “You want people to look at them and say, ‘Wow, where did you get [that clothing] from?’ ”

Arena conveys this sense of character more through his use of unusual vintage fabrics (precious finds range from zany striped cashmeres to a black-and-gold houndstooth with metallic thread) than through his cut, which is based on a classic aesthetic. Expect moderate lapels and clean lines. He trained under head cutter Brian Hall—whose name frequenters of Richard Anderson will recognise—at Huntsman in the ’90s and cuts using the Thornton System: a pattern-cutting technique that originated in the 1880s, which is based on the Victorian riding coat.

Arena’s jackets feature front darts that run from the chest right through the side pockets to the garment’s hems. This is unusual in British tailoring (front darts will more often run from chest to side pocket and stop there) but allows for more shape to be worked through the jacket’s front. Following his training at Huntsman, Arena went on to perfect his cut during an 18-year tenure as Paul Smith’s bespoke head cutter.

Alongside this pedigree, Arena is also known for his bespoke leather and suede garments—a one piece, knee-length, double-breasted suede coat called the Navona, is particularly striking, with its oversized collar, huge flap pockets and a chunky half-belt at the back (very Serge Gainsbourg).

“I always try to have new things in the studio, whether it’s a suede coat or a leather bomber or a beautiful bespoke jacket for people to look at,” Arena says. He adds that he wants clients to be excited when they walk through the door, rather than being faced with the “bland jackets” sometimes displayed in tailors’ shops.

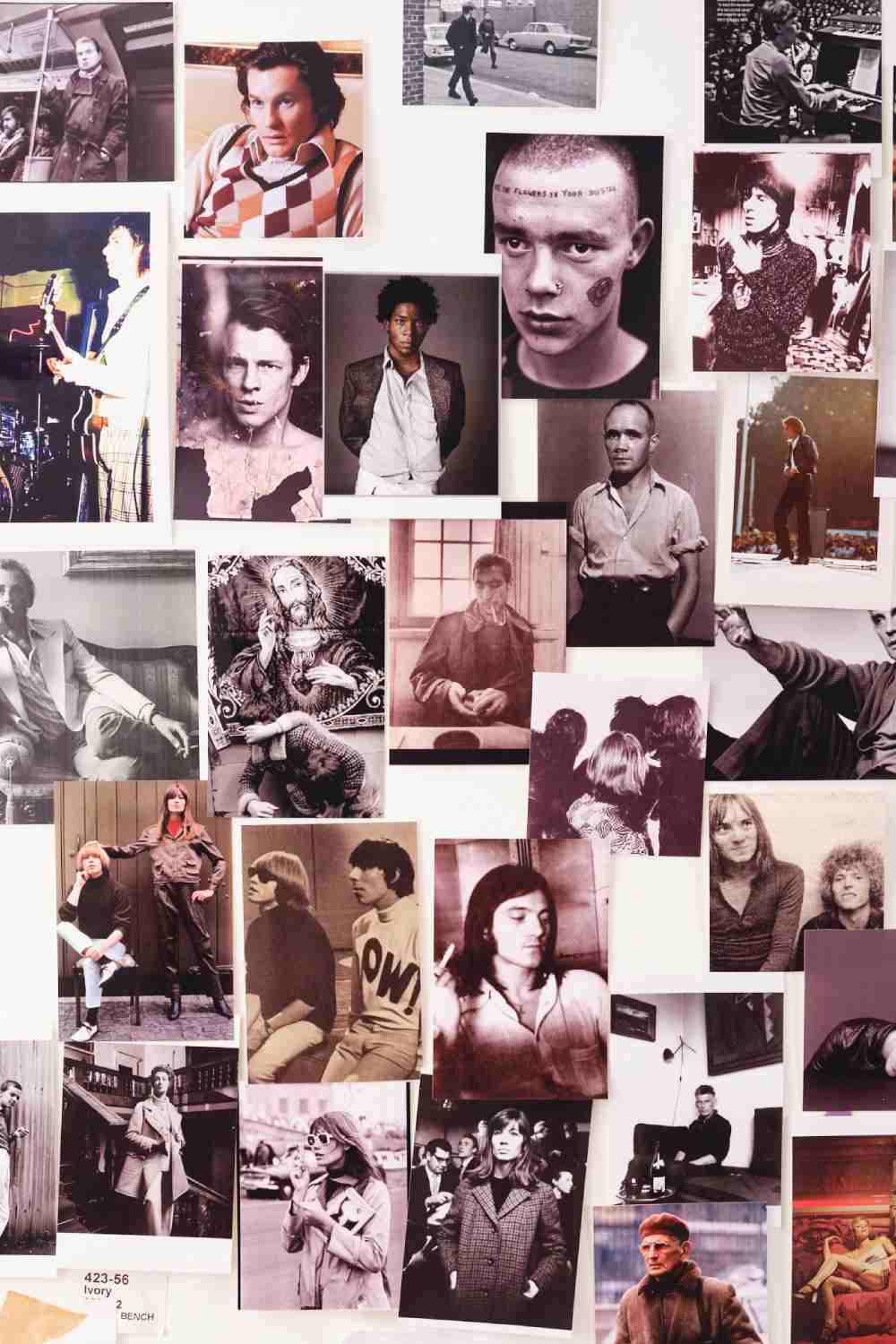

As with Lawton, the 1960s and ’70s are key reference points for Arena. His basement studio is located just off St. James’s, a stone’s throw from Savile Row, and has a cozy feel—almost like a hidden members’ club. The wall above his cutting table is covered with a montage of old photographs, album covers and film stills, with notables from James Baldwin to Charlotte Rampling on display.

Speciale

Speciale’s shabby-chic Portobello Road storefront, lined with oil paintings and stacks of vintage fabrics, feels more like a concept store than a tailoring studio. Step through a terra-cotta-hued archway into the belly of the space, though, and you’re in proprietor George Marsh’s atelier, which is every bit the artist’s studio. Half-finished coats, sleeves awaiting their jackets and off-cuts of cloth hang all around the walls on a copper rail.

Everything about Speciale is designed to emulate a Florentine neighbourhood tailor. Marsh, 31 (right, below), and his cofounder, Bert Hamilton Stubber, 29 (left, below), who runs the business while Marsh makes the clothes, worked together in London for four years, before moving on to different Florentine houses. Marsh, by this point, had spent two years studying under the godfather of Florentine tailoring, Antonio Liverano. “There’s so much expression in this style,” Hamilton Stubber says. “The hand of the maker is so visible because there’s that much more hand-stitching.”

The name Speciale is inherited from a late Florentine tailor who left no heir when he died to keep the moniker alive. “His last apprentice was a guy called Lorenzo Albrighi, who was the person who taught George,” says Hamilton Stubber. “George said, ‘I’ll resurrect the name, given I’m using his process.’ ”

True to the original Speciale, the present-day process of making a suit differs significantly from conventional London tailors—with the emphasis now on hand-assembling jackets and trousers. “I think in English tailoring, generally, the suit is defined by how it’s cut,” Hamilton Stubber explains. “The making is less important. Whereas in Florence, the cut is very simple. It’s just a single dart block [jacket design]. It’s really how a suit is made that gives it its life and character.”

Whereas most English tailors will use external workers, Marsh cuts, makes and finishes all Speciale’s suits by himself. His attention to detail is exceptional, with beautiful top-stitching by hand along the lapels and the extra-fine jets to pockets. Consequently, he averages around 160 hours on a single order.

A Speciale suit is perhaps best thought of as a low-key luxury. “I say it’s a well-thought-out cardigan,” Marsh explains. “It’s a lunch suit… it’s a suit for your most relaxed point in the day.” Because of the hours involved and the degree of precise hand-work, the brand currently only makes between 15 and 20 bespoke suits a year and supplements the business with sales of handmade shirts and limited-edition runs of knitwear.

Given the limit on how may suits he can make, Marsh is choosy about the garments he’ll create. “I’m quite strict,” he adds. “The main thing is working out the psychology of your client and the bits that they don’t know they want, or the bits they think they want and you know they don’t actually want. It’s kind of an interview process.”

The final result is worth the investment in time. Marsh’s jackets are the kind you’ll notice on the street not because they’re showy but simply because they exude a certain kind of elegance. Signor Speciale would doubtless be proud.

This article was first published on Robb Report US