Dr Chua Yang, daughter of Cultural Medallion recipient Chua Mia Tee, walks us through her passion for street photography and her debut exhibition, The Man Behind That Portrait

When I first enter the Leica Galerie at Raffles Hotel, Dr Chua Yang already has her camera out. She fingers it deftly, the way a musician routinely tunes an instrument. For a brief moment, I get a glimpse of her in her element – composed yet inquisitive, gingerly probing the next shot. Then she notices me and breaks into a jovial smile, letting the camera stoop gently down to her waist. Throughout the course of our interaction, it sits patiently, waiting; never once leaving her side.

For as long as she can remember, Chua has always had a camera with her – even on holidays as a child, when she and her father would each be carrying around their own, on the prowl for pictures that would later be shared between the two of them. “Of course back then I was much shorter, so I saw things from a different angle”, she laughs.

A practising obstetrician and gynaecologist, Chua’s love for photography deepened during her numerous medical missions around the world. It invoked within her a strong desire, as she puts it, “for better gear”, to evocatively capture the people, landscape and character of these often remote and obscure places. This led her to acquire her first Leica camera five years ago, an M240, which she describes as being “compact enough, quiet enough and discrete enough” – not “a big ‘thing’ with a huge lens” that would intimidate the many women and children she interacts with on her missions.

I can see why that would be the case: Chua’s M240 is a distinct bright red, along with its strap, and rests snugly in a maroon leather half-case – a warm, inviting touch to the black jacket that drapes across her shoulders.

In a broader sense, Chua’s choice of camera is revealing of her outlook and approach to street photography itself – more up close and personal, less removed and at a distance. “I like to get people to warm up to me”, she explains, “so I tend to sit down and chit-chat with them; to make an effort to get to know them, as opposed to ‘Hey, you look interesting, let me snap a photo of you’”.

Street photography, she says, “should be spontaneous, arising in the spur-of-the-moment”. “Sometimes you chance upon a character who passes by at the right moment leading up to a shot, and you are giddy with happiness”, she gushes. There is no fixed formula that dictates Chua’s oeuvre, no preordained poses or artificial lights – she does not even carry a tripod. “A shot that makes you happy”, she continues, “does not have to be earth-shattering or about making a statement. It should make you feel something – perhaps a warmth and fuzziness on the inside – and prompt you to think a little bit deeper”.

For Chua, it is this sense of authenticity and realism – the way a particular scene or person impresses itself upon her at a fleeting moment in time – that ultimately makes each photograph worthwhile; and which shapes the several photographs on canvas that enclose us in the intimate space of the gallery.

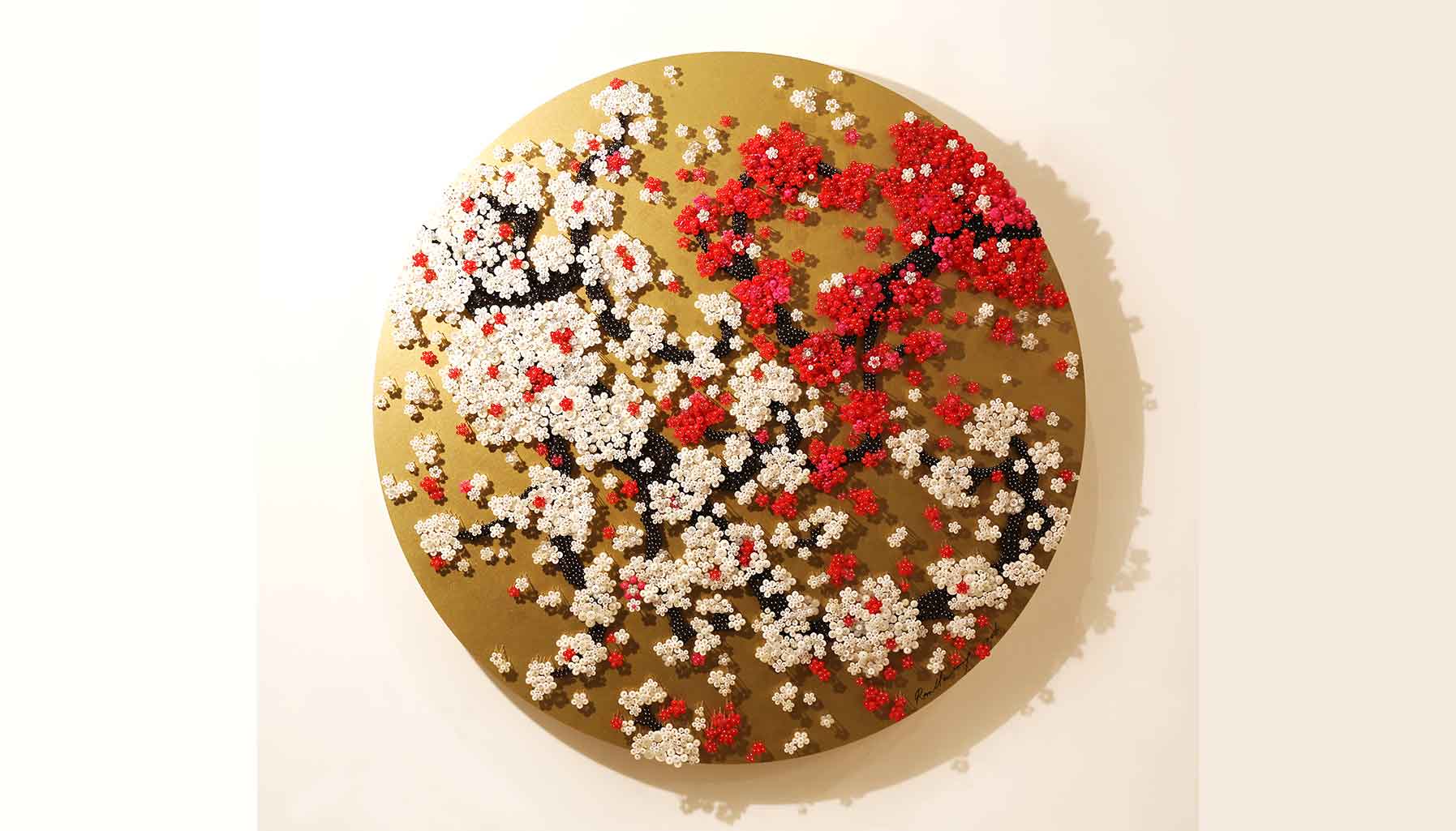

The Man Behind That Portrait – referring to Chua’s father, the prominent realist artist and Cultural Medallion recipient Chua Mia Tee – is her debut exhibition, offering viewers a raw, honest portrayal of her aging father in his day-to-day life. It is also a timely one, developed in conjunction with the elder Chua’s solo exhibition at the National Gallery Singapore, titled Chua Mia Tee: Directing the Real, which showcases his most iconic paintings.

“I have been taking his photos for a long time”, she says, “so these are part of a much larger collection. Most people would be familiar with his paintings, but I would also like them to know that behind an artist of his stature, is a man who is quiet at home and has his own routines. I wanted to represent the different aspects of his daily life, like the quietness of his studio and the fact that its configuration has not changed”.

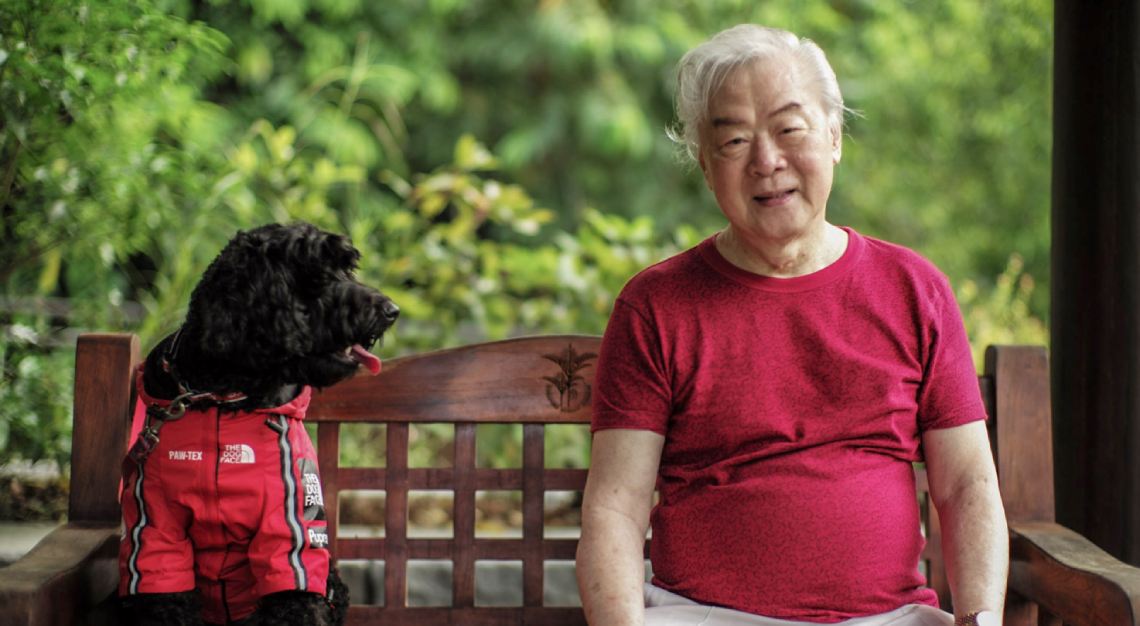

Through Chua’s lens, the poetry of the mundane is held still and magnified. Such ordinary moments as a shot of Tin Tin, her labradoodle, turning to face her father with “his pink tongue sticking out” during one of their regular morning walks at the Botanic Gardens. “You would not know this looking at the photograph”, she tells me, “but my dog rarely sticks out his tongue like that. So to capture that moment was the sweetest thing to me”.

Or the photograph labelled ‘Book Signing’, in which her father, at a formidable ninety years of age, grips his marker tightly, brows furrowed in concentration. To a friend of Chua’s who saw the exhibition, it spoke of “how difficult it already is at ninety”, where even “an autograph that he has signed a gazillion times” requires effort. And yet, contained within that simple gesture, is the same dogged determination and discipline that has driven her father’s single-minded pursuit of realism throughout his lengthy artistic career.

Even though she did not conceive of the photograph in this exact manner originally, Chua shares with me that such reactions are “precious to [her]”. “A work of art”, she maintains, “whether it be a photograph, a painting, or a piece of music, should speak to different people in a different way” – in much the same way that some of her father’s paintings are interpreted beyond his initial intentions.

As Chua continues walking me through the gallery, I am drawn to a photograph of her father seated beside a large window in the bedroom of his late wife and fellow artist, Lee Boon Ngan. Half-hidden by the shadows, he stares into the darkness, as if swallowed by her absence.

“There is a certain forlornness”, she admits, which is visible throughout the exhibition. But then she is quick to highlight its more positive currents. In one of the exhibition’s final photographs, her father is smiling, fingers circling to form an ‘O-K’ sign. “It is not really an ‘O-K’ sign, he was just doing his physiotherapy”, she reveals, referring to her father’s recovery after suffering a stroke in September this year, “but it was captured in a moment that looked as if he was giving me an ‘O-K’ sign. That element of positivity is what I like to show in my photos, which is largely influenced by what I do for a living as a health professional. I would like everybody to be healthy and happy”.

When I ask her what she hopes viewers will take away from the exhibition, Chua has little hesitation. “I think a lot of people do not take pictures of their family enough, especially their aging parents. Perhaps they are afraid to do so because they think their parents might object to it, but they really should not shy away from taking daily, routine photos. There is a lot of grace and resilience to be found in those moments, and that is as real as it gets”.

I get a sense of what this might feel like right before we part, as Chua quietly raises her camera and it lets out a gentle click, like a soft exhale one makes before turning to leave and walk away.

The Man Behind That Portrait is now exhibiting at the Leica Galerie at Raffles Hotel Singapore from now till 11 January 2022.

Chua Mia Tee: Directing the Real is now exhibiting at the National Gallery Singapore from now till 20 November 2022.