Robb Report’s editor in chief talks success, style, cars and career lows with one of the GOATs

Ralph Lauren is the most successful American fashion designer of all time, having built his brand upon an idealised, optimistic vision of America, a greatest hits of the 50 states, which he disseminated throughout his homeland and exported around the world. But such is Lauren’s global influence that labelling him merely an American fashion designer feels miserly. Because isn’t Ralph Lauren simply the most successful living designer, fashion or otherwise, in the world?

Name another. In Europe, Giorgio Armani arrived not too long after Lauren and has had arguably as much impact on men’s style over the years, by ripping the heavy canvas out of his suits and sending the deconstructed jackets of Neapolitan bespoke tailors into the mainstream. But didn’t Lauren actually get there first, fashioning soft blazers to emulate his Hollywood heroes? Lauren was first to create a homewares line, too, and released his debut fragrance a few years before Armani. Philippe Starck, Tom Ford, Norman Foster, Miuccia Prada, Dieter Rams? Innovators, of course, in their fields, but Lauren stands above them all. If you include those no longer with us—well, that’s a longer conversation for another time: Yves Saint Laurent, Gio Ponti, Loe Corbusier, Coco Chanel, Enzo Ferrari, Karl Lagerfeld… But even there, Lauren’s is the name that won’t go away.

For now, let’s agree on this—Ralph has done OK. An example: Sometime over the Atlantic on a recent red-eye, I made, in hindsight, an odd choice of sleeping aid—watching the high-adrenaline Rocky sub-franchise Creed III. I was struck by one scene, an image of the film’s hero—former heavyweight champion of the world Adonis Creed, played by Michael B. Jordan—towering over the highway on a multistory billboard advertisement for Ralph Lauren. As a shorthand for global domination, it was pretty effective.

Lauren’s story has been told well and often, but it’s hard not to repeat a few salient facts, because to understand the origin story is to make sense of everything that followed. He grew up in the Bronx, the son of Russian emigrant parents. “When I was a kid, I dressed well,” he says. “I knew how to wear clothes, and that was unusual. I don’t know why I knew it.” His first job out of school was as assistant salesman at Brooks Brothers, and by then clothes were his obsession. Indeed, designer, author, and menswear authority Alan Flusser, in his exhaustively researched book Ralph Lauren: In His Own Fashion, quotes a coworker at Lauren’s next job as saying, “He may have been making 40 or 50 dollars a week, but he dressed like a million bucks.”

Lauren is no product of fashion school; his talent was always instinctive. “My boss at the time made neckties up in Boston, and I asked them to give me a shot,” he recalls. “I was 24 years old and believed in everything I was doing. He didn’t think my things were that good. I asked him if I could design a line, and he said, ‘The world is not ready for Ralph Lauren.’ ”

But Ralph Lauren was ready for the world, so he set out on his own. It was 1967, and he came up with a range of neckties that bucked the prevailing fashion: His were wide at a time when skinny was in. Famously, he sold them from a drawer in a room in the Empire State Building. “I didn’t think about success, because I was so far away from success. I made ties. Just getting a tie into Bloomingdale’s was success.”

This happened soon enough, but not before he’d walked out on the buyers when they insisted he remove his label and replace it with theirs. By 1970, now with full collections of shirts, pants, and suits under his belt, Lauren was the first designer to have his own discrete boutique in Bloomingdale’s. A year later, he debuted the concept of the standalone designer store by launching Polo by Ralph Lauren on L.A.’s Rodeo Drive.

“I loved what I did. I loved the product, I loved designing it,” he says. “My friends were wearing what I was making. I knew I had the style. I loved the Duke of Windsor and Fred Astaire. Movies were very inspirational to me… I actually made the clothes I couldn’t find. I couldn’t find the Duke of Windsor [style] anywhere. I knew what he looked like, but you couldn’t walk into a store and buy a double-breasted blazer or tweed suit or suede elbow patches.”

Now, when you look at images from the 1920s and ’30s of the duke in Fair Isle knits, tweed sport coats, and soft suiting, you see a handshake between British country elegance and relaxed American athletic and Ivy style. And what springs to mind is that, 50 years before there was such a thing, the whole ensemble feels “very Ralph Lauren.” In fact, the notion of “very Ralph” could likely be understood not just by those with an interest in fashion but by anyone who has spent time in a shopping mall, browsed magazines, or watched TV in the past three or four decades, such is the visual legacy created by Lauren and photographer Bruce Weber, who shot so many iconic campaigns. For that reason, Very Ralph was also the title of a 2019 documentary about Lauren’s life.

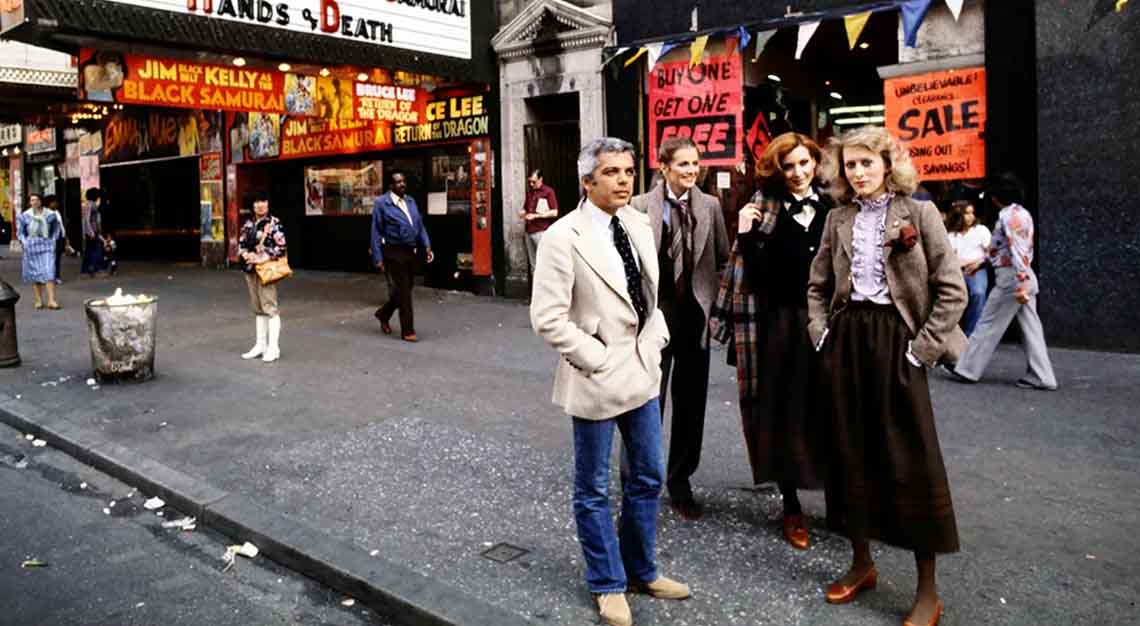

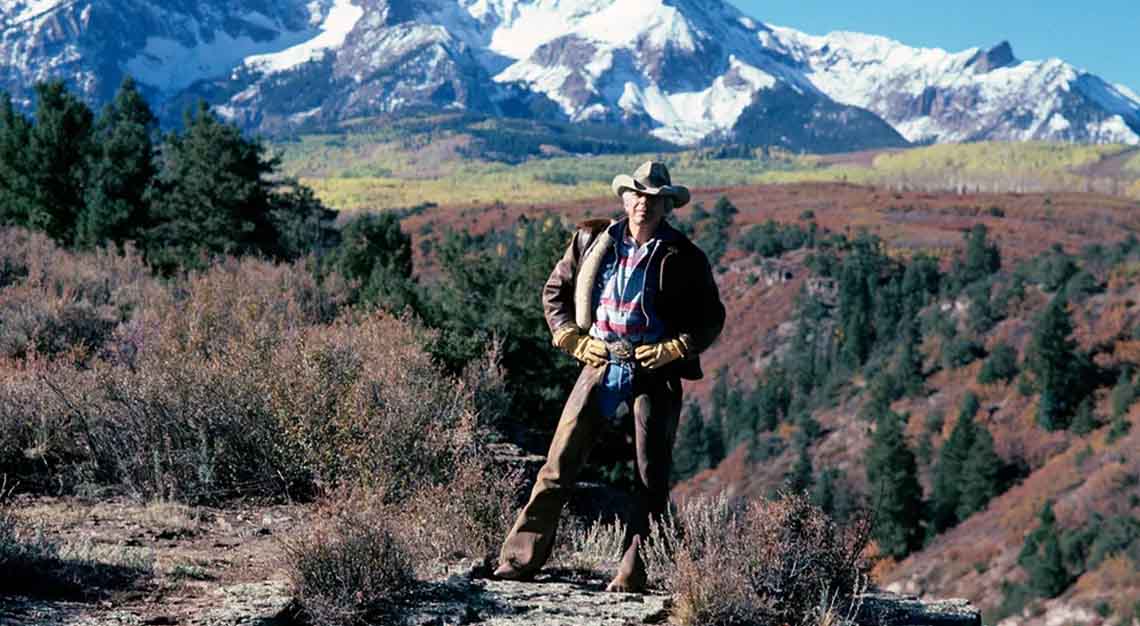

Lauren achieved something that nobody had done before and few, if any, have done as well since. This was to sell the aspiration inherent to the product: the elegant élan of a double-breasted suit; an at-one-with-the-land existence via a pair of chinos; an entire preppy universe, free with a button-down oxford shirt. It has become prevalent enough that we know it when we see it, whether depicted via the uptown glamour of New York City or ranch life in Colourado, the boats and beaches of Nantucket, the Ivy League college campus, or even the playing fields of English private schools. Ralph Lauren has designed the U.S. Olympic teams’ uniforms since 2008, but for decades before that and since, he has been the official clothing supplier of the American Dream.

“I loved things that were American,” he says with passion. “I loved jeans when no one loved jeans. I saw that all people knew about America was they make blue jeans. Americans are not known for fashion. They’re known for practicality, for utility. They’re good at that. I loved that, too.”

It wasn’t always this easy, of course. Not everyone got it, not for a while. Marrying tailoring and denim is commonplace now, but 40 years ago it was iconoclastic. He received a Coty award for womenswear and a Coty Hall of Fame award for menswear in the same year, 1976, but even there, the recognition was tempered.

“I remember going up to get one of the Coty Awards, it was a big deal at the time,” he says. “And the woman from The New York Times said, ‘What are you wearing?’ I was wearing blue jeans and a tuxedo jacket. Those things are old news for me now. But she didn’t get it. It was brand-new. The designers got it, other people got it, but the [American] magazines were not really with it. And the magazine editors, they liked what they saw in Europe.”

It’s something that still rankles. “Well, as years have passed, I’ve been hurt a little bit, but I can’t walk around and say, ‘Listen to me, everybody, I did this.’ But I did,” he insists. “I did all those things. I think I made my mark, but I kept moving. I kept doing new things. I went from ties to shirts to suits, to menswear to womenswear to restaurants. I mean, that had never been done.” From slick suiting to the ubiquitous polo shirt to streetwear, from bed sheets to side tables, rugs, and rocks glasses, and from the Polo Bar burger to a Polo bear sweater for your puppy, Lauren’s vision has, it seems, touched everybody.

We’re sitting on tan leather armchairs with carbon-fibre arms (his own design, in homage to one of his favourite cars, the McLaren F1, more on that later) in his offices on Madison Avenue, surrounded by trappings of the recognition that initially eluded him—awards, framed campaign imagery, model cars, coffee-table books, and other “very Ralph” objects. Soon to be 84, he still does relaxed style better than most: khaki safari jacket, grey-marl jogging pants, white New Balance sneakers—unmistakably Ralph. His hair, unchanged for decades, remains white and abundant. The eyes are a little softer now, and the memory at times not as quick, but talk of style or cars sets him alight.

In any story of success, failure has had at least a walk-on role. When I ask him to share some lows, Lauren goes back. “Well, when I was starting out, the business was in trouble,” he recalls. “I started with a US$50,000 loan from a company. So I started with not a lot. Today, US$50,000 is a hamburger. But I remember, all of a sudden, the banks are calling me saying, ‘Ralph, you don’t have enough money in the business.’ I was doing it alone, and I was worried about what my father was going to think. He was so proud of me…. So I had to sell a piece of the company to Goldman Sachs. And they supported me; they helped me through the tough time. It was like giving up one of my children. I gave a few kids away. But I got them back.”

There have been other challenges, of course. “I’ve been doing this for 56 years,” he says at one point. “Can you believe that?” Amid falling sales and criticism that the brand hadn’t evolved, Lauren stepped down as CEO in 2015, remaining executive chairman and chief creative officer. Little more than a year later, his replacement, the former global president of Gap’s Old Navy business, Stefan Larsson, was gone. The man at the top now is Patrice Louvet, who has been in place since 2017. But Lauren retains design oversight, as he’s quick to remind me when I question it.

“Oh, yeah—I work on the collections,” he confirms. “But I have great designers that have worked for me for 30 years. Having all the things that I have, you have to have a team you can rely on. I’m happy with what I’ve built. I’m proud of the company.”

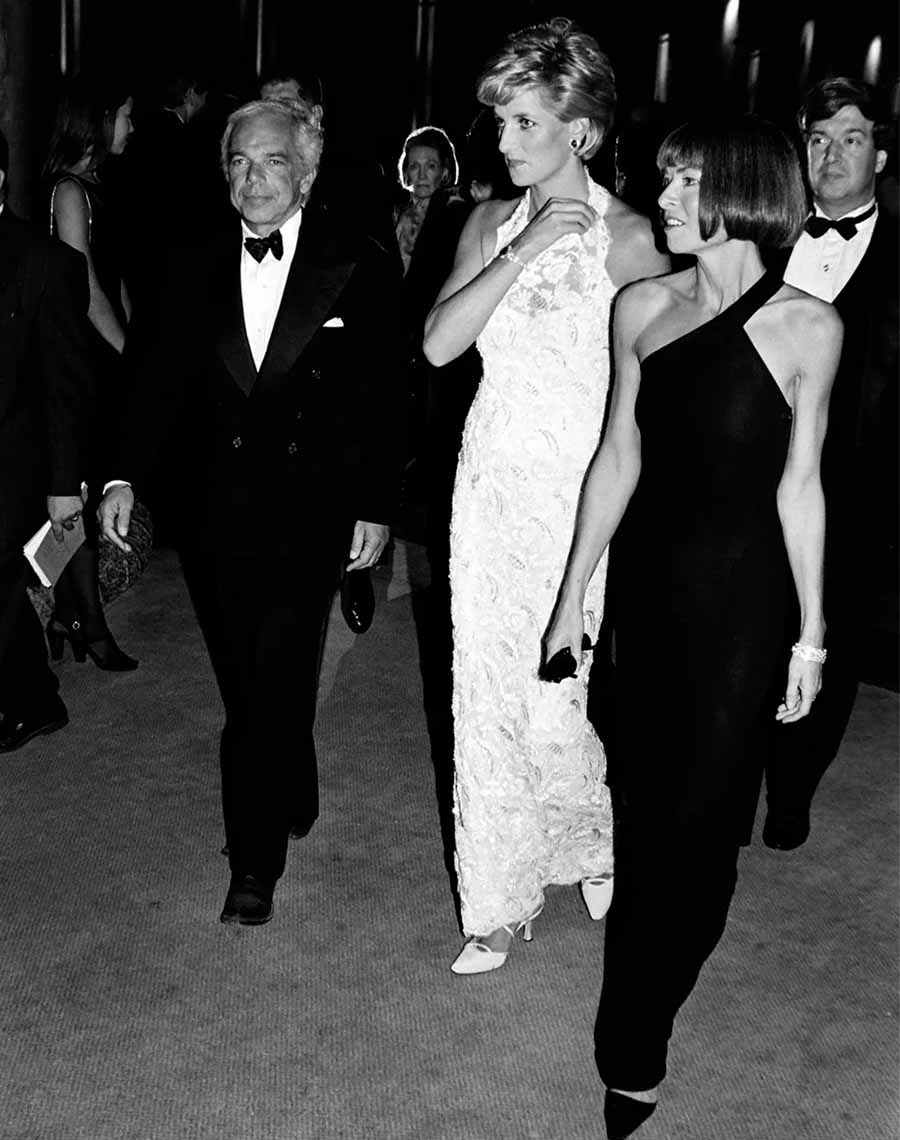

One thing of which he can be truly proud is that Lauren was one of the first designers to use people of colour in fashion campaigns. “I didn’t have that kind of sense of Black and white,” he says, “but I knew there were no Black models in the industry. There were some Black models occasionally on the runway, but not in ads or not representing brands.” That changed in 1993, when Lauren employed a young Black model with Chinese ancestry named Tyson Beckford, giving him a significant contract after Beckford boycotted Milan fashion week in protest of the lack of inclusion there. He went on to be the face of Polo Sport fragrance and the first Black male supermodel. But three years before that, Lauren had cast Rashid Silvera, a Black teacher, originally from Boston, and avid collector of Polo clothing, in several campaigns and has used him ever since. “I believed in the world. I know what it is to be…. ” Lauren pauses here. “I’m Jewish. I know the differences, the way the world was—and still is.”

There have been critics over the years, of course: For example, some claimed the company was guilty of cultural appropriation in its use of Native American imagery and heritage. (Ads featuring historical Native American figures were pulled in 2014; the Ralph Lauren Corporation issued an apology.) The company has since launched a cultural-awareness council and an external Native American & Indigenous Advisory Council, both of which aim to help it achieve best practises.

Did you see the cars?” Lauren asks, with a gleam in his eye. He’s referring to his cars, in his garage complex in upstate New York, where the fashion story that accompanies this interview was photographed. Access to this automotive wonderland was offered by Mr. Lauren himself—no publication has shot a fashion story here before. He and his wife, Ricky, read Robb Report, and I have been planning this feature with his team for a number of years. So, yes, I had seen the cars. In fact, I’d gawped at their 100-plus-year histories as you might the combination of a collection of old masters and contemporary art in a gallery.

Over two floors of this automotive Louvre, there are dozens and dozens, with an almost incalculable value. They are immaculate, restored to perfection, attended to by a team of technicians and curators. The lineup reads like an inductees list for a four-wheeled Hall of Fame: Mercedes-Benz SSK “Count Trossi.” The 300 SL “Gullwing” Coupe. The 300 SL Roadster. Bugatti’s Type 57SC Atlantic Coupe and Gangloff Drop Head Coupe. Jaguar’s superlative XK120 Alloy Roadster. And XKD. And XKSS. And Ferraris—so many Ferraris. Deep breath: 375 Plus; 250 Testa Rossa; 250 TR 61 Spyder Fantuzzi; 250 GTO; 250 LM; 250 GT California Spyder; 250 GT SWB Berlinetta Scaglietti; 2015 LaFerrari; 275 P2/3 Spyder Drogo; F40… And Porsches, Morgans, Bentleys, and multiple McLaren F1s. There are side rooms with old trucks and jeeps and more Porsches and the convertible Mercedes that he bought his wife for her graduation. “I was just a guy wanting to buy a car,” he says. “I wanted a Morgan. I wanted an MG. I loved those when I was a kid.”

There was a definite Anglophile aspect to his early purchases, just as there was to his general aesthetic, but there’s more to it than just that. “I believed in England and in the sensibility,” he says, “but I was an American with the sense of taste, a mix. So there’s the English Americanness.”

“There were cars I was able to buy because I took the chance. I started to make some money and, instead of art, I bought cars that I could afford, and I had them restored to where I dreamt they should be. I didn’t think I was going to have a major collection. I just took chances with cars that I thought were beautiful—they were art to me. And turned out some of the values just kept going up and up.”

Any collector of anything, particularly cars, will recognise the truth in the following statement: There’s always a story. Take the Bentley Blower. Lauren starts to tell a tale of being around Washington Mews, just north of Washington Square Park in Manhattan, many decades ago, and seeing guys in helmets driving these extraordinary-looking cars. “And I said, ‘What is that? I want that.’ I had to go to this house in England, belonging to the guy who owned an old Bentley. It was a hard sale: I thought I lost it. But the Bentley was a symbol of something that I really loved.

“The cars were my dream: They got to be a fever. The Mercedes Gullwing, that was one. Also, it’s the car I think I look like. I look like that Mercedes in my brain. And I also look like the Jaguar XK120. And the 140. And the 150. I had to have it right. So when I got the 120, I said, ‘I got to get the 140.’ I was insane with my cars.”

Of course, insanity is all relative. But in case you doubt him, here’s another story, this time about the F1.

“Every day after my dinner, I would go and look at the McLaren in the window of the showroom,” he recalls. “I was dreaming about that car. But you couldn’t get it. Maybe that’s why I got so crazy. You couldn’t get them into America. I spoke to the head of McLaren at the time. I said, ‘I really want to get this car.’ And he said, ‘You have to take the car apart.’ ” This was due to safety and emissions legislation that requires some foreign cars to be dismantled and modified before being imported legally into the country. So he did.

“I went and picked it up from the factory with my wife. Tom Cruise was in town, and the McLaren guy said, ‘Tom Cruise is looking—he might get one.’ And I said, ‘Then I better get another one, because my kids are going to kill me later on that I didn’t get them the McLaren.’ ” Which is why he has more than one in his collection. “It turned out to be an amazing, very expensive car. I paid a million dollars, and you’d think I was crazy. It’s now worth, like, US$30 million.”

And yes, he does drive them, often taking one from his place in Bedford, N.Y., to his garage on the weekend, swapping it for another, and piloting that one until the urge strikes to change it up again. And yes, the collecting bug is still strong. “I got a new one,” he says. “It’s on its way, but I won’t see that for probably a year. That’s the only car I’ve bought in the last few years—the Gordon Murray T.50.” Murray, for the uninitiated, came up with the concept for the revolutionary F1, with its driver’s seat front and centre. He left McLaren to set up Gordon Murray Automotive and, with it, produce the T.50, the spiritual successor to his previous masterpiece. After being unveiled in 2020, the T.50 only went into full production in March of this year, and just 100 models will be made. That Lauren will soon be driving one should be of no surprise to anybody.

I mentioned earlier that it wasn’t always so easy for Lauren. One of the major crises of his life was the diagnosis of a brain tumour back in 1986. It was ultimately declared benign, but a couple of years later a regular checkup revealed that it had begun to grow and needed to be removed. Not long after his successful operation, he bumped into Nina Hyde, a Washington Post editor he knew, who told him she had breast cancer.

“I got very emotional about this,” he recalls. “You have to know in this wonderful world, pain can come. I knew this woman. I liked her. She was smart. And I felt like, ‘I can help her. She won’t die. I’m going to get the money.’ I had a brain tumour, I know what it was like to feel, ‘Oh, my God—how did I get this?’ And I kept [funding cancer research], and it started to grow as a part of my life. There wasn’t a reason to do it, except that I felt like I was so successful, I could help her, too. I really believe you can do a lot of good things in this life: It can’t be ‘me, me, me’ all the time. You got to give back.”

In 1989, he cofounded the Nina Hyde Centre for Breast Cancer Research at the Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Centre in Washington, D.C. Hyde died the following year, but Lauren doubled down. In ’94, he helped establish Fashion Targets Breast Cancer with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designing the logo and raising $2 million via sales of 400,000 Ralph Lauren FTBC T-shirts. The Pink Pony Fund of the Ralph Lauren Corporate Foundation was established in 2001, aimed at reducing disparities in cancer care across different communities. The Ralph Lauren Centre for Cancer Care launched in Harlem in 2003, in partnership with the nation’s leading cancer centre, Memorial Sloan Kettering, after Lauren learnt that a disproportionate number of cancer patients were dying in that neighbourhood due to a lack of local treatment options (it has since become the MSK Ralph Lauren Centre).

Further collaborations and donations followed, including with the Royal Marsden in London, the largest cancer centre in Europe; and the Johns Hopkins Centre for Indigenous Health to advance care in tribal communities; as well as a US$25 million pledge to create or develop five more centres across the U.S. Other corporation-wide philanthropic initiatives include environmental protection and diversity and inclusion.

It’s nearly time to go. Lauren has a dentist’s appointment. I have one last question: He’s mentioned his wife, Ricky, often. Family is a huge part of what Ralph Lauren, the man, is all about. His three kids—Andrew, 54, who works in film; David, 51, who works for the company as chief branding and innovation officer, president of the Ralph Lauren Corporate Foundation, and vice chairman of the board of directors; and Dylan, 49, a businesswoman and founder of Dylan’s Candy Bar—have appeared in campaigns all their lives, and Ricky has been ever present by his side. His muse. They’ve been married 59 years. Tell me about her, I ask.

“She’s going to read this article, so I got to butter her up,” he says with a grin. “She supported everything. She’s not a fashion person—never really cared about it. She reads a lot. She’s a psychotherapist. She’s very beautiful and real. Life is not perfect, but she’s been very great. And my kids are very nice people.”

Perhaps that is what success is really about for Ralph Lauren. For all that the brand he has built has conquered the world, bringing him spoils and acclaim (according to estimates, he is worth well over US$8 billion), in the end, when you think of Lauren, his family is never far behind. As I walk down Madison back to Robb Report’s offices on Fifth Avenue, I’m reminded of something he mentioned halfway through the interview.

“There’s no movie to this. This is not a fake thing,” he said. “It’s not a brand. It’s my life.”

This story was first published on Robb Report USA