Chefs around the world, from Stockholm to Singapore, are returning to one of the oldest and most primal methods of cooking, and derive inspiration from the distinct flavours that only smoke and flame can impart

It couldn’t be further removed from the last decade’s obsession with sous vide when it seemed almost rude to be aware that the chef was cooking. Cooking on flaming wood is visceral and almost invariably becomes the focal point in the dining room. Cast aside any preconceptions that open-fire cooking is simple. It takes great skill to be an alchemist with direct heat.

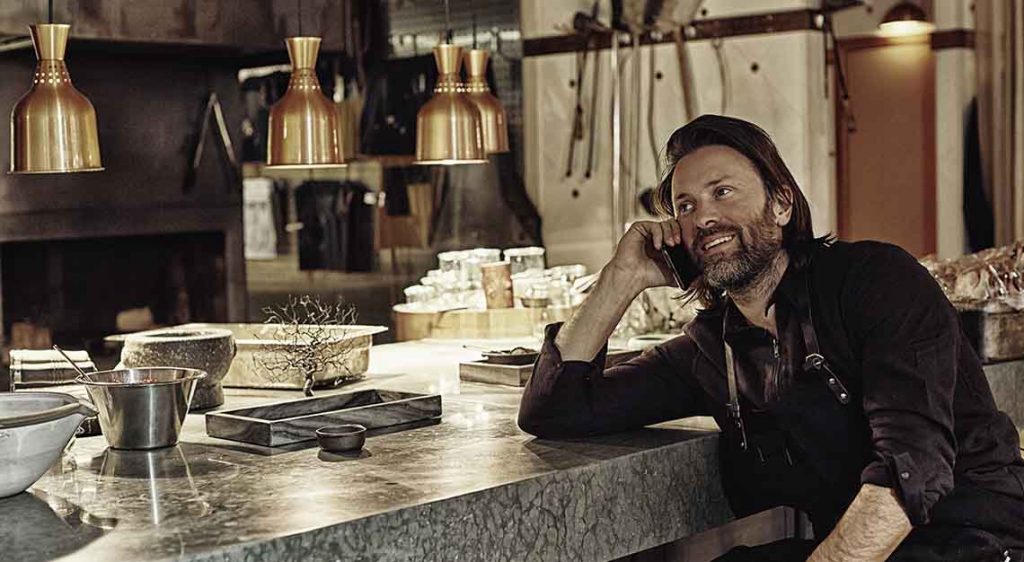

Transforming Food With Fire

“Every time I cook with fire it is different. The heat becomes an active ingredient in each dish and every time it cooks differently. That’s what makes it so exciting and technically challenging to the chef,” says Tomos Parry. His new restaurant Brat in London’s Shoreditch has wowed critics. Parry openly acknowledges that he is hugely influenced by Basque open fire techniques.

Like many chefs firing away worldwide, he cites time spent at Asador Etxebarri as a life-changing pilgrimage. There, deep in rural Basque countryside, he learnt from self-taught fire master Victor Arguinzoniz, who even designed and built his own giant cooking racks. He is credited with igniting the almost cultish obsession with varying the wood to impart different fruit flavours to cook giant Palamos prawns, outstanding beef chop and even ice cream.

Getaria, a small coastal village is another hearth of pilgrimage where some of San Sebastian’s top chefs such as Elena Arzak and Andoni (of Mugaritz fame) are known to eat. I’ll never forget visiting with a gang of the world’s best chefs – including Albert Adria and Fergus Henderson – during the San Sebastian gastronomic festival. Everyone was totally mesmerised watching multiple turbot on individual fish-irons tended on a giant well-seasoned grill outside the venerable Elkano restaurant. Explains second-generation chef-proprietor Altor Arregui, “No fish is the same, it calls for precise understanding, a light touch. Having to judge minute changes for perfect fish every time is technically challenging”.

Back at Brat, Parry cooks each turbot slow and low for around 40 minutes to allow the collagen to gradually dissolve and the skin take on a toffee-like quality, while the flesh remains firm and succulent. To serve he sprays the fish with a vinegar mix that adds a distinctive tang to the skin and juices and creates a subtle emulsion sauce. As at Elkano, Parry encourages diners to eat everything including the cheeks and throat.

What may surprise many is the nuanced complex layering of flavours, the mix of umami and sweetness, the charred giving a play of delicate bitterness against the richness. Parry even finishes his signature unctuous baked cheesecake by charring it over fire.

Taking A Cue From The Past

Parry is not alone in cooking over fire; in fact, it’s all the rage in the English capital. At Pitt Cue Co, the restaurant that started out as a street food truck, chef Tom Adams cooks his own curly haired, mangalista pigs reared at his Cornish farm over open flames. Neil Rankin uses this cooking method older than civilisation at his Temper restaurants. He commissioned vast hulk-like ranges with grids and spits almost as large as a fire engine and cooks everything from flatbreads to goat and fish. “I cook slower, lower and longer for a subtle finish.”

Though it is odd to call it a trend since flames are the oldest way of cooking food, Scandinavian chefs too are embracing wood fire cooking. Niklas Ekstedt of Ekstedt in Stockholm cooks cutting-edge Scandinavian food while banishing electricity from his dining room and reverting to ancient Norse techniques. He cooks only in a wood-burning oven dating back to the 1870s, over a fire pit or smokes ingredients through a chimney using birch wood.

The best seats are at the counter in close proximity to the compelling flames and his batterie of cast iron cooking gear. Oysters cooked in ox fat and seaweed are like kissing the sea. Equally daring are diced reindeer hearts with tart lingonberries and spiced butter offered as a snack. Best of all are hay-baked scallops licked by flames with juniper-fermented cabbage, brown butter cream and spicy horseradish juice sprinkled with charcoal dust.

The Francis Mallmann episode of the Netflix docu-series Chef’s Table had audiences worldwide entranced by the renowned Argentinean chef’s theatrical open-fire cooking at his restaurants across South America and his newest at Chateau La Coste, a 647-hectare luxury estate with an open-air art gallery outside Aix-de-Provence. Originally trained in French classical cooking, Mallmann returned to the elemental ways of his native Patagonia, and was inspired by traditional gaucho (cowboy) indigenous cooking.

A Growing Trend

Mallman has inspired a growing number of chefs around the world who are elevating wood-fired cooking to new heights. Logs pile to the ceiling in the courtyard of Bestia restaurant, which recently opened in the outskirts of Buenos Aires. Its co-owner, chef Nacho Trotta, travelled for weeks through Alabama, Louisiana and Texas to incorporate the smoking and grilling methods of US southern cuisine into dishes that he slowly cooks for more than 10 hours. “Firewood is the engine of this restaurant,” says Trotta. “It is not all char and smoke, fire can be far more subtle in the way it concentrates and accentuates flavour.”

At Chicago’s El Che Bar, John Manion looks to Argentina’s urban parrilladas (barbecued meat) and rural asados (the tradition of having a barbecue event) for inspiration, too. Also in Chicago is Lena Brava, Rick Bayless’s ode to the barbacoa (a cooking method) of Baja California Norte, Mexico. Live fire licks the ingredients in salsas and sides that accompany fire-roasted halibut and massive tomahawk beef rib chops.

Brooklyn’s Metta whose chef, Norberto Piattoni worked for Mallmann, is oriented around a wood fire that delivers seasonal California-meets-New Nordic dishes like charred beets with rye berries, and roasted fish with turnips and nettles.

At Firedoor in Surrey Hills outside Sydney, Etxebarri-trained Lennox Hastie uses grapevine, and fruit trees like peach and orange. Smoke is a constant presence, yet controlled precisely in dishes such as a delicate salad of shaved fennel and cells of finger lime with seared albacore or marrow bone roasted over coals until on the verge of melting and mashed into grilled bread with some fermented chilli and a few sprigs of peppery salad greens.

Chef-patron Dave Pynt of Singapore’s Burnt Ends has done time with culinary heavyweight Etxebarri. As ever the best seats in the house are at the counter marvelling at the custom-built elevation grills and wood-fired ovens. Best of all is Burnt Ends’ Sanger: extraordinarily delicious fluffy brioche buns, juicy pulled pork and smoky chipotle – an extraordinary balance of flavours. “Fire just makes a difference, says Pynt with a glint in his eye, and that’s really the most important thing.