The global art market has a long and colourful history, but how far has it come since then and where is it heading?

For someone who has built a career in the professional art world in London and Singapore, it would be an understatement to say that the global art market has witnessed unprecedented growth in the last two decades in terms of volume of sales. Additionally, the industry has experienced a surge of newly minted art collectors from across the globe in every major city and capital, who often traipse around the world for art fairs, important museum shows and swanky art parties to hob-nob with celebrity artists and the international art glitterati.

This special community of people who share a common passion for art collecting is increasingly led by a tribe of young, hungry, tech-savvy and brand-conscious consumers. In fact, the art world is starting to look a lot like the fashion world, where groups of close friends or colleagues travel together like a pack; moving cohesively as a group to make their pilgrimage to the latest art fair or biennale.

A Look Into The Past

If we look back over the last century, the art world was a very different place. At the turn of the 20th century, Paris was growing into a hub for artistic innovation. By the 1920s, the left bank of the River Seine was home to various young galleries, and the city thrived with interesting artists, wealthy patrons, museums and local auction companies.

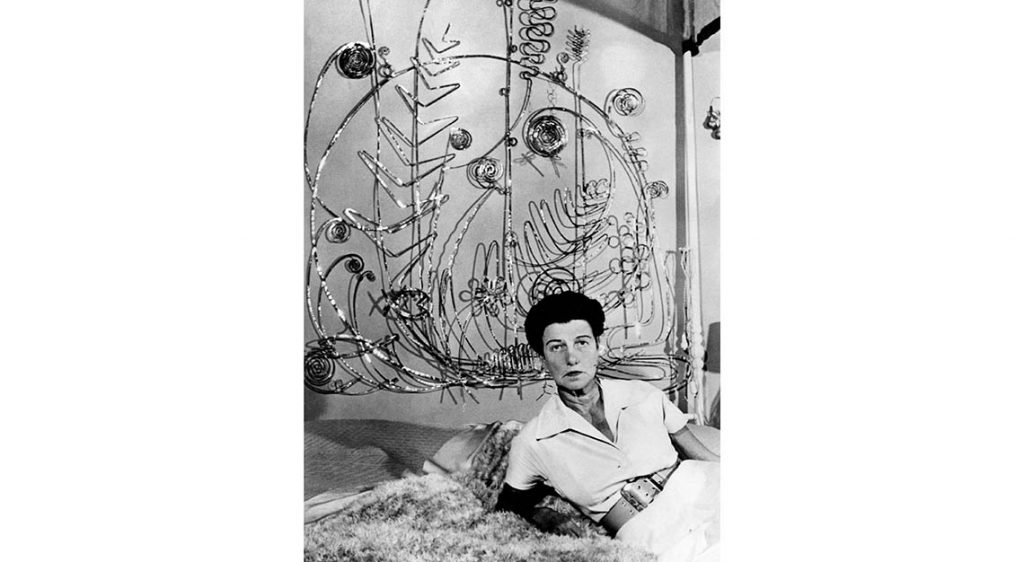

Paris was a key market for contemporary art of its time – today we call these movements impressionism, post-impressionism, symbolism and cubism. When World War II broke out in the early 1940s, the Paris and London art markets slowed down as many Europe-based Jewish dealers were forced to flee, with some choosing to relocate their business to New York.

New York benefited from the Jewish exodus from Europe, as collectors like Peggy Guggenheim and dealers such as Pierre Rosenberg and Joseph Duveen sought refuge and made the American city their new home. These influential dealers advised American private collectors such as Andrew Mellon and John Pierpont Morgan. It was inevitable then that New York succeeded Paris as the most exciting centre for modern and contemporary art in the post-war era.

Since the 1970s, the perception of art as a moneymaker or good speculative investment has gathered pace as a result of several developments: a series of economic boom periods and cycles where liquidity is high and funding cost is low, an increasing number of international art collectors and the expanding globalisation of the market, with each of these factors contributing to the growth and strength of the global art ecosystem.

The Calm After The Storm

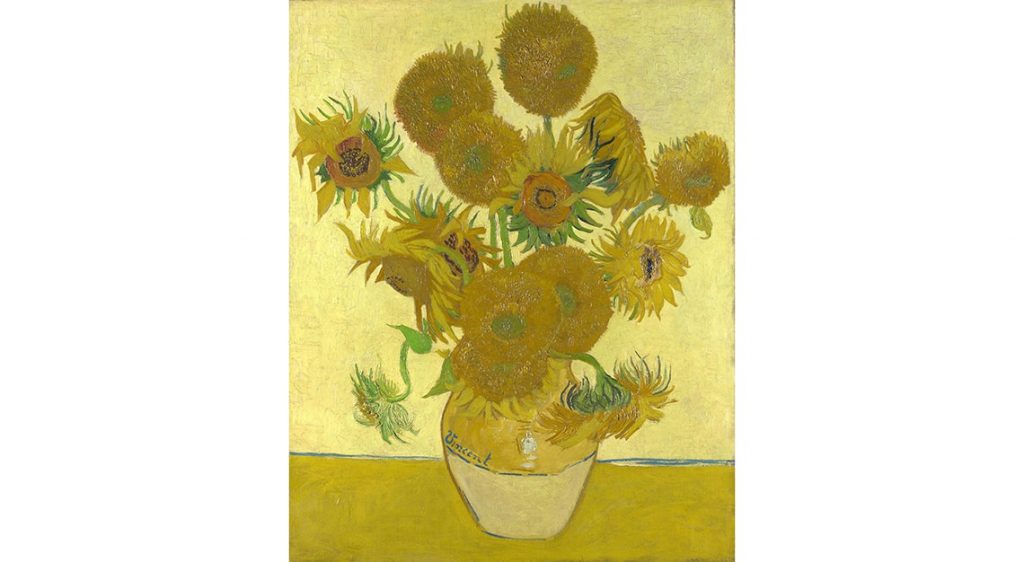

In the 1980s, there was an extraordinary boom in the art market, with money pouring in from institutions and individual buyers for works within the impressionism and post-impressionism movement. During this time, Japanese buyers became a significant presence in the auction salerooms. It was a unique moment in time, as the Japanese yen was re-evaluated in 1985, and in 1986, US tax law removed incentives for wealthy individuals to donate fine art to museums. This instigated them to unload blue-chip artworks to the market.

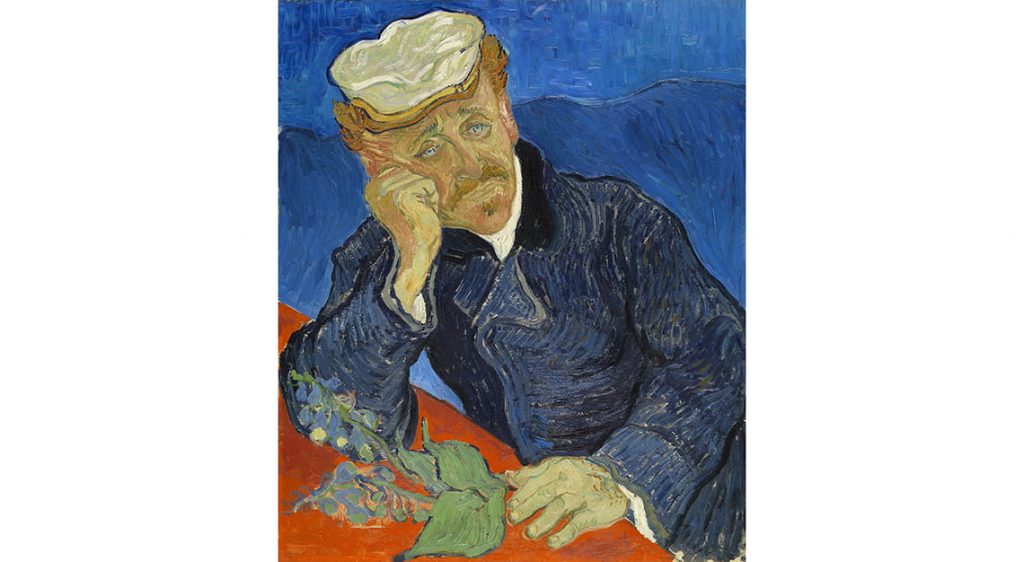

When the stock markets crashed in 1987, prices of impressionist artworks escalated, and Vincent van Gogh’s paintings became a Japanese favourite. Sunflowers was sold to the Yasuda insurance company for US$40 million (S$54.3 million), and a prominent Japanese businessman bought Portrait of Dr Gachet for US$82 million (S$111.3 million).

https://www.instagram.com/p/BspcFxdAtSc/

During this period, certain banks also accepted fine art as collateral. If you owned a US$10 million (S$13.5 million) painting by Picasso, it was possible to secure a US$5 million (S$6.7 million) loan without having to part with the painting. Naturally, savvy businessmen with enviable art collections saw this as a great way to raise cash for investments or as a means to acquire more art. This quiet phenomenon in the art market could partly explain why Japanese investors were buying up blue-chip paintings in the 1980s. However, this buying could not be sustained and, eventually, the bubble burst.

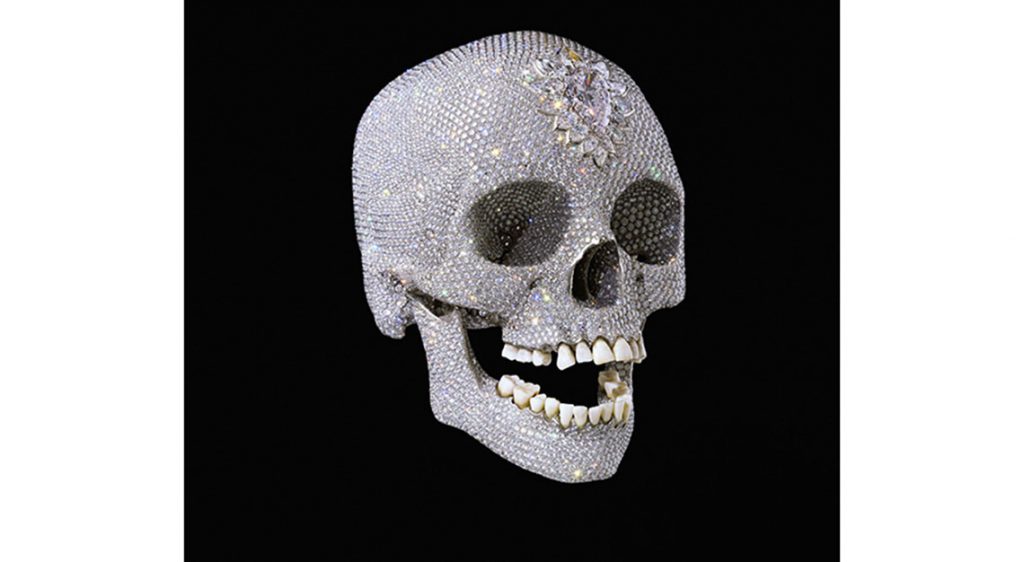

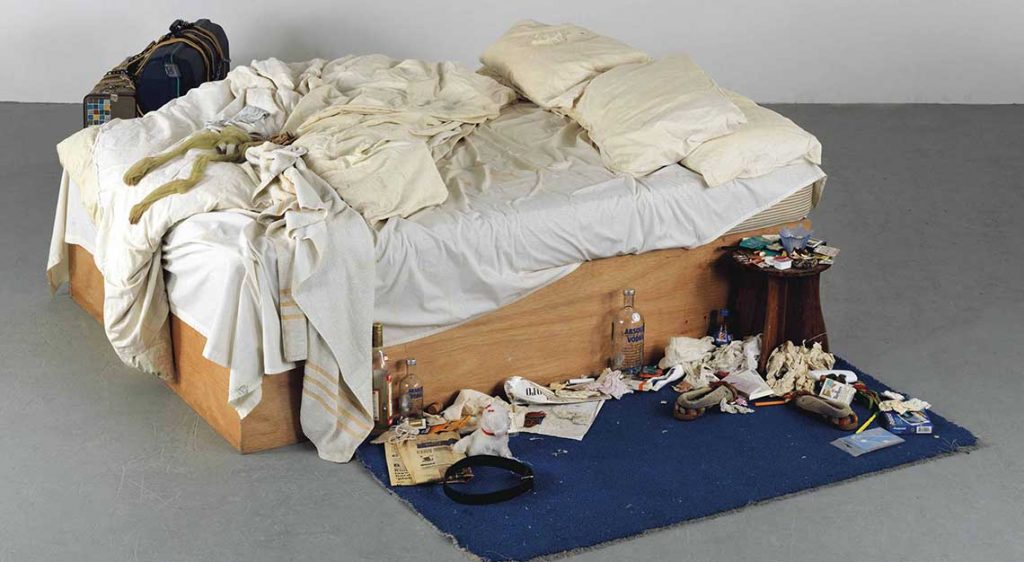

The Japanese buying sprees were a precursor to the art market’s biggest growth sector, leading to the rise of contemporary artists and artworks from the early 1990s. In London, artists such as Damien Hirst, who gained international notoriety for his formaldehyde shark and diamond-encrusted skull, and popular female British artist Tracey Emin – whose work My Bed was shortlisted for the Turner Prize in 1999 – became international stars.

Collectively these artists belonged to the Young British Artists (YBA) group and benefited greatly from the patronage of advertising guru Charles Saatchi, founder of Saatchi and Saatchi agency. The YBA generation also received a boost from the opening of the Tate Modern in 2000.

When Art Met Finance

In the early 1990s, art fairs were organised as B2B industry events to generate more sales. But today, art fairs are an important fixture on the international circuit and for anyone who has a vested interest in the buying, selling and acquisition of art.

Art fairs have a wide offering and quality is ensured by a vetting committee – an important criterion when collectors decide which fairs to visit. Here, prices are transparent and much of the experience is shaped by social encounters with artists, by bringing friends along or through networking with other art buyers.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BrVo2HMhuBM/

As art fairs grew to become popular lifestyle events in the West, it was only a matter of time before financial institutions such as UBS, Deutsche Bank and other luxury brands such as Cartier and BMW would jump on the opportunity to sponsor major art fairs such as Art Basel and Frieze. Big financial companies and private wealth management firms like Julius Baer also saw the prospect of offering bespoke art advisory services for their clients.

This can be attributed to two key drivers: the first was that there was a correlation with banks such as UBS and Deutsche Bank, which understood the commercial and brand value of their enormous corporate art collection – the current count of the UBS art collection stands at 30,000 pieces – and secondly, banks were responding to the increasing demand from their HNW clients who were keen to diversify their investment portfolio into alternative asset classes such as art.

The post-2000s has seen the emergence and growth of private art funds. In fact, in a study conducted by Deloitte and ArtTactic in 2014, it was found that there were an estimated 72 funds in operation, 55 of which were Chinese funds, with the remaining funds holding a combined value of more than US$400 million (S$543 million) in art assets under management.

Today, many of these funds have come and gone, but the Fine Art Fund, founded in London in 2003, remains one of the most stable and established platforms for savvy investors. The fund claims to be the first investment vehicle to experiment with investments into the art market at a scale similar to the British Rail Pension Fund during the 1970s and the 1980s.

A Glimpse Into The Future

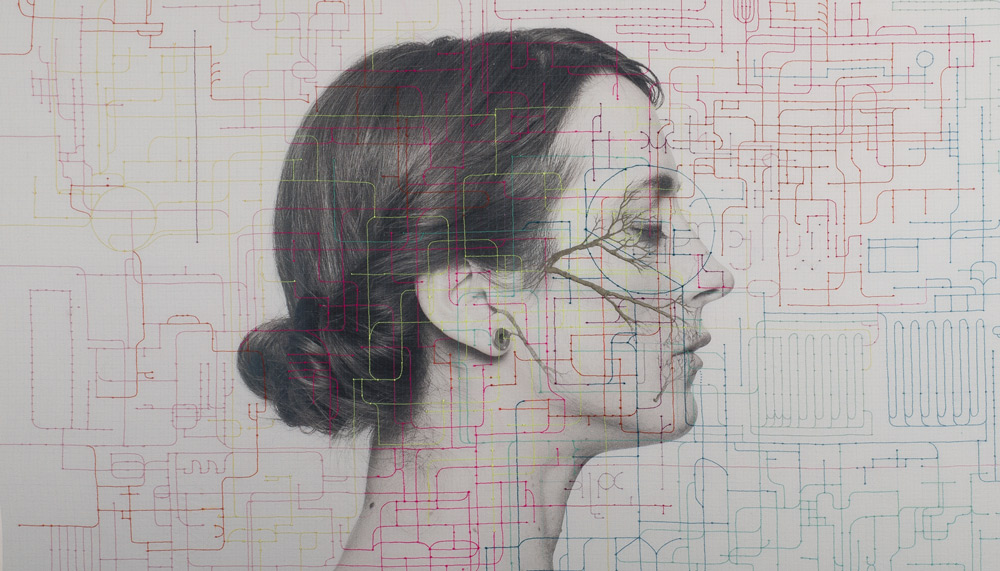

These days, it’s hard to talk about art and finance without taking technology or cryptocurrency into account. Recently, the market has seen numerous start-up online platforms offering consumers direct access to artists from all over the world from the comforts of home. Some entrepreneurs have taken it to the next level by further democratising access to fine art works through blockchain technology in a bid to tokenise fine art.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BudqLNKFkRC/

One such example is Maecenas, a Singapore-based company that claims to be the first technology-driven business to bridge the gap between art and finance by offering collectors increased liquidity, lower transaction costs and more transparency. In the summer of 2018, Maecenas made headlines when it tokenised an Andy Warhol painting and put it on auction, allowing 100 participants to invest in it. The painting was appraised at US$5.6 million (S$7.6 million), and the auction raised US$1.7million (S$2.3 million), which is approximately 31.5 per cent of the painting’s overall value.

What’s the biggest difference between today’s environment and everything before 2000? The answer is simple: it’s the advent of the Internet and social media. Now more than ever, marketing and promoting art on social media wield greater influence over the perceived value of art, and key opinion leaders strive hard to maintain active and interesting social media accounts – posting backstage access to exclusive events, placing value on being spotted and reported about by other influencers at the right parties and acquiring pictures or ‘wefies’ with the hottest and most in-demand artists. This is how high-profile prominent individuals influence what other collectors buy, which ultimately boosts an artist’s commercial prospects.

Headline-grabbing sales results and publicly available prices have prompted new and experienced collectors alike to get into contemporary art collecting – many of them with at least some thought to its profit potential. In the past, there was an emphasis on connoisseurship, knowledge, aesthetics and taste when collecting as an investment. Today, the trends have shifted, with a greater emphasis on amassing empirical price information and being able to gauge market trends when collecting art.

A famous quote by Warhol comes to mind: “Making money is art, and good business is the best art.” Today I can fully appreciate this quote and if I had the chance at a do-over in life, I would still choose to be in the art business.

Ning Chong is the founder of The Culture Story, a boutique art consultancy that provides advice and project management services to corporate and private clients.