Four of the world’s greatest collectors of all things shiny, glittery, and fancy

How easily impressed we were as kids, when pirates’ treasures and lost jewels in adventure stories fit into mere chests. As adults, the truly wealthy aficionados are much more insatiable. Numbering in the hundreds, or even thousands of pieces, theirs are the collections that fill private showrooms, galleries, and even entire museums.

Far from personal greed, many collect out of true admiration for these masterpieces. After all, jewellery is an important part of the history and evolution of decorative art. Through their loans and donations to exhibitions around the world, these collectors have made valuable contributions to public education that go beyond the monetary value of the jewellery they own.

Al Thani

To call the Taj Mahal a building would be an understatement; to say that it’s the world’s grandest mausoleum is to merely state a fact; declare it a giant walk-in safe with gems embedded in its walls is to most accurately describe it.

The treasures of the Mughal Empire are world-renowned and what’s seen at the Taj Mahal are just the tip of the iceberg. There’s more where they came from, and there’s one man with enough wealth and determination to amass them all: Sheikh Hamad Bin Abdullah Al-Thani, a cousin of the Qatari emir, and CEO of Qipco, a holding company with interests in the financial and real estate markets.

It all began in 2009 with a serendipitous invitation. Al-Thani was asked to attend an exhibition titled Maharaja: The Splendour of India’s Royal Courts at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Then only 27 years old, he had never been to India, but the unbridled opulence on display had him immediately enthralled – and unlike most visitors to the exhibition, he didn’t have to limit himself to just looking. Today, little more than 10 years later, the Al-Thani collection is widely considered to be the most encyclopedic private collection of Mughal treasures in the world.

In June last year, a Christie’s event titled Maharajas & Mughal Magnificence gave those with deep-enough pockets a chance to get their hands on almost 400 items from the collection. The sale fetched a total of US$109 million (S$157.71 million), which, according to a statement by Christie’s, was “the highest for any auction of Indian art and Mughal objects, and the second highest for a private jewellery collection”. The top lot was 277, a Cartier brooch from the Belle Epoque era that realised a breathtaking US$10 million (S$14.46 million).

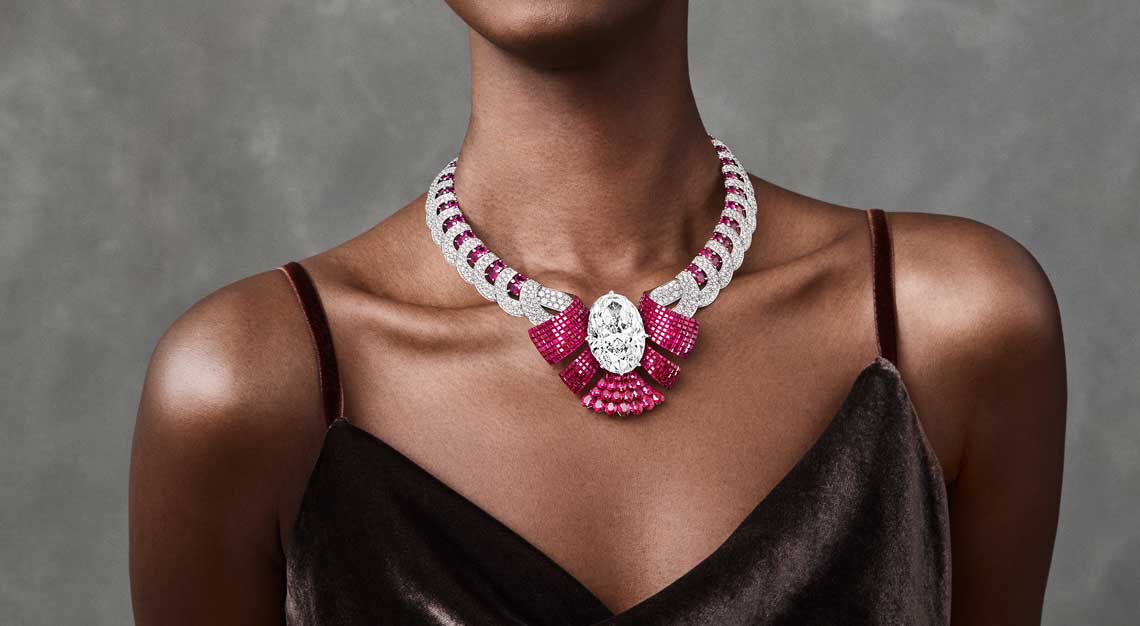

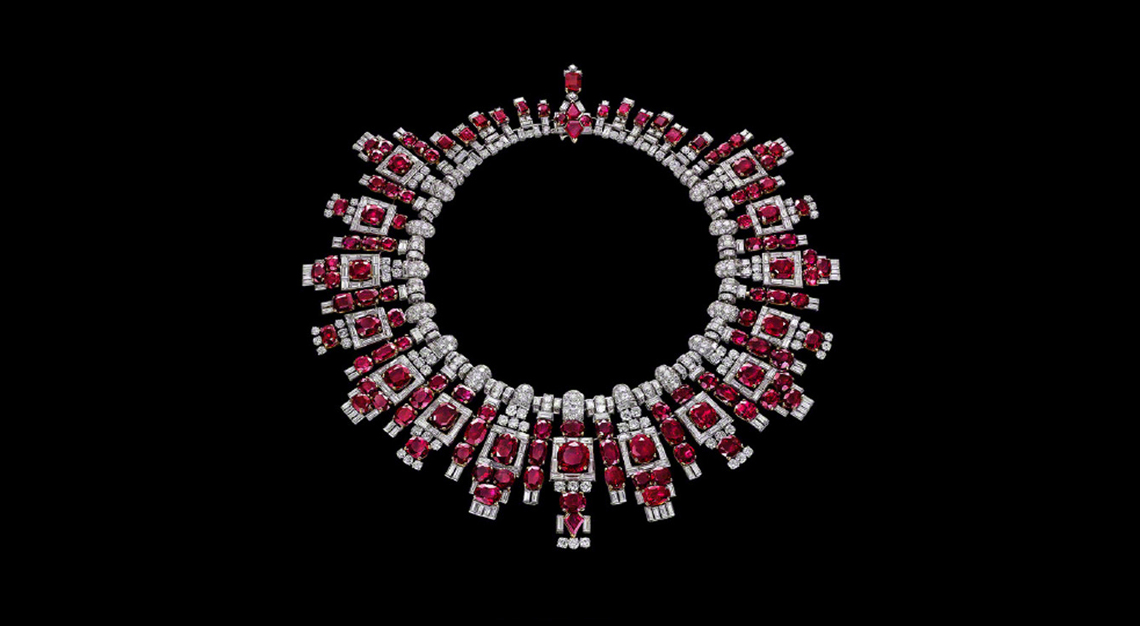

Even after the sale, more than 6,000 items remain in the Al-Thani collection. Two exceptional pieces include the Nawanagar ruby necklace made by Cartier in 1937 for Maharaja Digvijaysinhji featuring 119 gum-drop-sized Burmese rubies, and the 70.21-carat Idol’s Eye, the world’s largest faceted blue diamond, that, according to legend, was taken from the eye of a statue of a Hindu deity.

Since 2016, these masterpieces and their counterparts have been managed by the Al Thani Collection Foundation. Through its support, the collection has been shown at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, The Palace Museum in Beijing, and The State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, among others. In spring this year, the collection will move to its new permanent home, a 400-square-metre gallery in Hotel de la Marine at the heart of Paris.

Elizabeth Taylor

Besides her beauty, Elizabeth Taylor was probably most famous for two other things: her love for spectacular jewellery and her seven husbands from eight marriages (she married Richard Burton twice). Luckily for Taylor, smitten members of the latter group were often more than happy to shower her with the former, especially her fifth husband Richard Burton, who also became her sixth following a reconciliation after a short divorce.

Perhaps most renowned among her collection are the various emerald pieces by Bulgari; the actress seemed to have an affinity for both the gem and the brand. “I introduced Liz to beer, she introduced me to Bulgari,” Burton had famously joked about his blossoming relationship with Taylor while on the set of Cleopatra.

For their engagement in 1962, he gifted her a brooch from Bulgari featuring a 23.44-carat step-cut Colombian emerald surrounded by diamonds. This piece went on to make multiple appearances, including as a pendant attached to a necklace Taylor received from Burton for their wedding two years later. Also from Bulgari, the necklace had 16 step-cut Colombian emeralds adding up to 60.50 carats that matched the one on the brooch-turned-pendant. Probably her most-worn piece featuring her favourite green gem however, was a pair of earrings with two pear-shaped emeralds totalling 20.64 carats. She wore them to a party for the 1961 Spartacus film, the premiere for Lawrence of Arabia in 1963, and a meeting with the Queen in 1976.

In December 2011, nine months after Taylor’s death, the Elizabeth Taylor Trust raised US$156.8 million through the sale of her estate with Christie’s New York. Called The Collection of Elizabeth Taylor, the event had 1,778 lots, all of which was sold. Twenty-six of the pieces went for more than US$1 million. The jewellery portion alone pulled in US$137,235,575 (S$198,362,359), taking the record for the most valuable sale of jewellery in auction history.

The top lot was the La Peregrina pearl, which dates back to the 16th century and sold for US$11,842,500 (S$17,117,327), shattering auction records for historic pearls and for any pearl jewel. Purchased by Burton for “just” US$37,000 (S$53,480) at an auction in 1969, it used to be a part of the Spanish crown and is believed to have been once owned by Mary Tudor of England and the Bonapartes of France. When Taylor received it, she commissioned Cartier to mount it on a necklace with rubies, diamonds, and 60 round pearls.

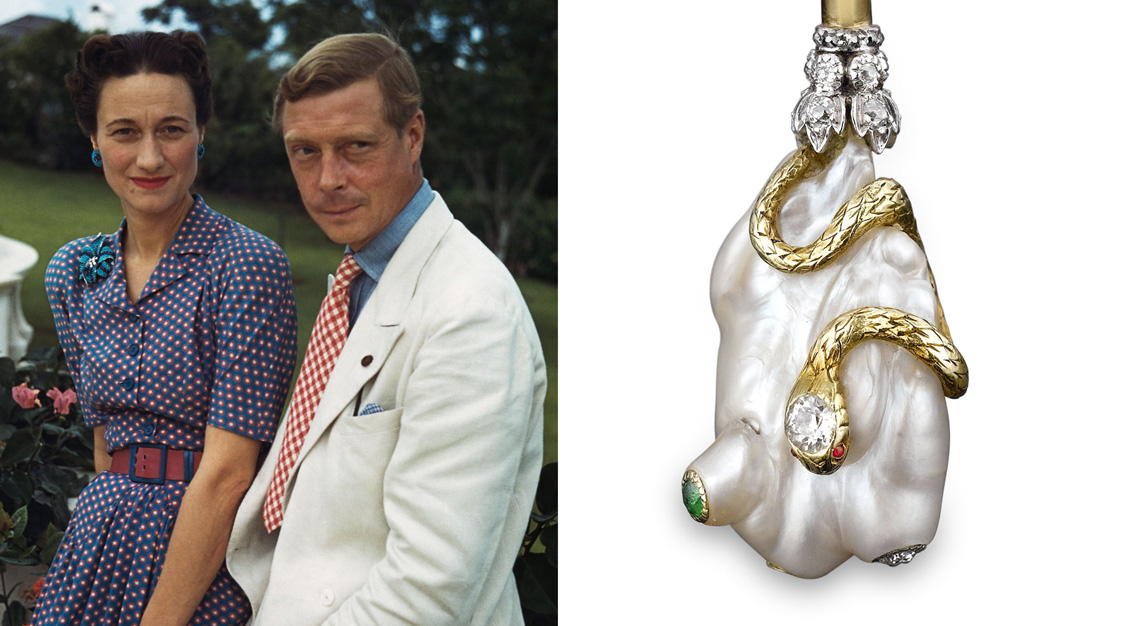

Duchess of Windsor

As if getting a king to fall so utterly in love that he abdicated to marry her wasn’t achievement enough, there were three other things Wallis Simpson did very well: wearing expensive jewellery, making an entrance, and making an entrance by wearing expensive jewellery.

Before she became the Duchess of Windsor, she famously showed up at the royal box at the opera house bedecked in a necklace with diamonds and emeralds so big, it got tongues wagging – mostly to say that the gems were not real, but just glass and paste. The naysayers had grossly underestimated King Edward VIII’s generosity towards her and the lengths he would go to show his devotion for her.

The duchess had a special fondness for French jewellery, namely, Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels. From the former, she favoured the Panthere pieces, and owned a diamond bracelet set with onyx for the leopard spots. When worn, it resembled a panther curled around the wrist. From the latter, she had a platinum, white gold and diamond necklace with a tassle of rubies. Given to her on her 40th birthday by Edward VIII, it was engraved with the words: “My Wallis from her David 19.VI.36”.

Little less than a year after her death in 1986, the duchess’ collection was put up for sale in a Sotheby’s event titled Jewels of the Duchess of Windsor. It included 87 pieces by Cartier and 23 pieces by Van Cleef & Arpels, among others. The engagement ring Edward VIII gave her, inscribed with the message “we are ours now” and set with a show-stopping 19-carat emerald, was one of the lots. It sold for US$1.98 million (S$2.86 million).

Among the buyers was Elizabeth Taylor herself. In commemoration of her friendship with Simpson, she purchased a diamond brooch she had always openly admired. Fashioned into the crown of the Prince of Wales insignia adorned with its three feathers, the brooch cost her US$623,327 (S$900,966).

In total, the 1987 sale of the duchess’ jewels saw proceeds of US$50 million (S$72.27 million), a record for its time. In accordance to Simpson’s will, the money was donated to Pasteur Institute in Paris for AIDs and cancer research. More of her collection has since come up for sale in various auctions, mostly as one-off pieces from private collectors. The last themed sale exclusively featuring Simpson’s items was in 2010. Again hosted by Sotheby’s, it brought in £7,975,550 (S$13,587,266).

Kazumi Arikawa

Few – if anyone – can say that jewellery is essential to survival with a straight face. Kazumi Arikawa does, and he’s so convincing, one is tempted to believe him. It could be the sage manner of his delivery, no doubt a remnant effect of the two years he spent as a Buddhist monk in his twenties. According to him, beautiful jewellery can give people “heart-shaking inspiration”, encouraging them to strive for the same perfection in themselves, thus making the world a better place.

Far from living the ascetic life of a monk, Arikawa is, today, the president of Albion Art, a preeminent dealership for historical Western jewellery spanning the Greco-Roman to Art Deco eras. His collection of 800 pieces, which he generously allows visitors to his private showroom to hold and touch without gloves, is complemented by an extensive library of 6000 books – many of them rare – on the decorative arts.

One of the most important pieces is a Fabergé tiara he bought 30 years ago, prized more for its sentimental, rather than monetary, value. Not that it was cheap – it cost Arikawa half the value of his entire (much smaller) collection then, and he had to scrape the money together. It was a risky purchase as tiaras were, at that time, considered unfashionable. But Arikawa was sure about what he liked, and the impulse buy has proven to be a good move; today, only four Fabergé tiaras remain and their rarity makes them highly valuable.

Above any type of jewellery, cameos and intaglios are Arikawa’s favourites. He considers them the height of artistic achievement and owns around 50 pieces of them, mostly dating from the 18th and 19th centuries. A recent spree at London dealer Wartski’s has added a few museum-worthy Greco-Roman examples to the collection.

Arikawa is always keen to share his treasures, and was the main sponsor for The Body Transformed exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2018. Last year, he contributed his Art Deco pieces to L’ecole Van Cleef & Arpels for its Lacloche exhibition in Paris. Some time next year, Arikawa intends to open a research centre in Paris to give jewellery scholars better access to the rare books in his collection. Ultimately his goal is to found a museum in Kyoto to showcase his jewellery collection, the scale of which, he imagines, will earn it the nickname of The Louvre Museum of Jewellery in Japan.