His journey with the company began in 1972, and by opening up the Middle Eastern markets, he stewarded IWC safely through the Quartz Crisis and beyond

The saying that ‘pressure creates diamonds’ cannot be more apropos for Hannes Pantli, member of the board of directors for IWC Schaffhausen. The jovial 77-year-old joined the company at the start of the 1970s, which was literally the worst time to embark on a career in luxury watchmaking. With the grip of the impending Quartz Crisis ever tightening on the industry, numerous companies faced a real threat of going bust, IWC included.

Then in charge of sales for Switzerland, Benelux and Scandinavia, Pantli decided on the bold move to break into the Middle Eastern market, in order to sustain the company’s coffers. Armed with a suitcase full of watches, he visited Qatar, Bahrain, Abu Dhabi, and Oman five to six times annually. On each visit, he’d meet up with the sultans and sheiks to build a relationship and better understand their likes and dislikes.

https://www.instagram.com/p/ByfezJunma-/

He recalls, “I would show them our watches and they’d go ‘this is old, that is old… where’s all the new stuff?’ So I knew that we have to create something special for them.”

Very quickly, Pantli returned with special watch sets created just for that market. There were cases of bejewelled ladies’ watches set on a gold chains and paired with rings. There were cases of men’s diamond-set watches delivered with rings, cuff links, key chains and writing instruments. This time around, he had come with the right products, but faced yet another challenge.

“I got a message from our CFO who said if I didn’t bring back a hundred thousand Swiss francs in sales by the 20th of that month, we’ll be officially out of business,” he recounts. Thankfully, the stars were shining down on him. Pantli sold the pieces, brought the money back, and slowly they saved the company.

Throughout the 47 years he’s been with IWC, Pantli never lost his love for the brand. In fact, to date, he remains hopelessly devoted to the watches. Vintage watches, including IWCs, in particular, are a source of constant fascination. He was once the proud owner of an amazing collection that included hundreds of IWC watches. Indeed, over 300 watches in the IWC Museum in Schaffhausen belonged to Pantli.

Right around the time when Richemont took over IWC, the new management made him an offer to buy up the collection.

“It was my private collection,” he sighs. “But Richemont convinced me to sell. [The watches were] part of the history of the company and they had no collection, so I said ok. I sold 310 IWCs to Richemont. But the most beautiful ones? I kept.”

Pantli has however agreed to loan his prized possessions to the IWC Museum to be on permanent exhibit or tour. Most recently, at the IWC Vintage Pilot’s Watches exhibition in Kuala Lumpur, seven out of the 12 historical watches belong to his personal collection.

Just in town to catch up with clients and visit the market, Pantli sat down with Robb Report Singapore for a quick chat.

What was your earliest memory of IWC?

There’s a tradition in Switzerland where you would get your first real watch from your parents once you turn 15. I was in boarding school. All my friends got a watch, all from brands everybody knew. Only one person (me) got an IWC. They were, like, what the heck did you get? What is this Schaffhausen? They laughed. But my father said, if you don’t know what Schaffhausen is, that’s your problem. I never forgot that. Years later, I was approached by a headhunter, and he also said, if you don’t know what IWC is, that’s your problem. That really came back to my mind. So I started in this small place called Schaffhausen, and it’s almost 50 years now.

How much has the company changed since the pre-Richemont days?

We were independent. But in the culture not much has changed. Of course, the world is changing. Everything is digital, more international, faster… But I would say the spirit of IWC hasn’t changed much. I think it has got to do with the fact that we are away from the centres of Swiss watchmaking. If you’re in La Chaux-de-Fonds or Geneva you constantly hear a lot of things, some are true, others not. We are a little bit away from that, so it gives us a chance to be different also in the way that we think. Of course we are in a big group now, but I think mentally, not much has changed.

What were some of your proudest moments at IWC?

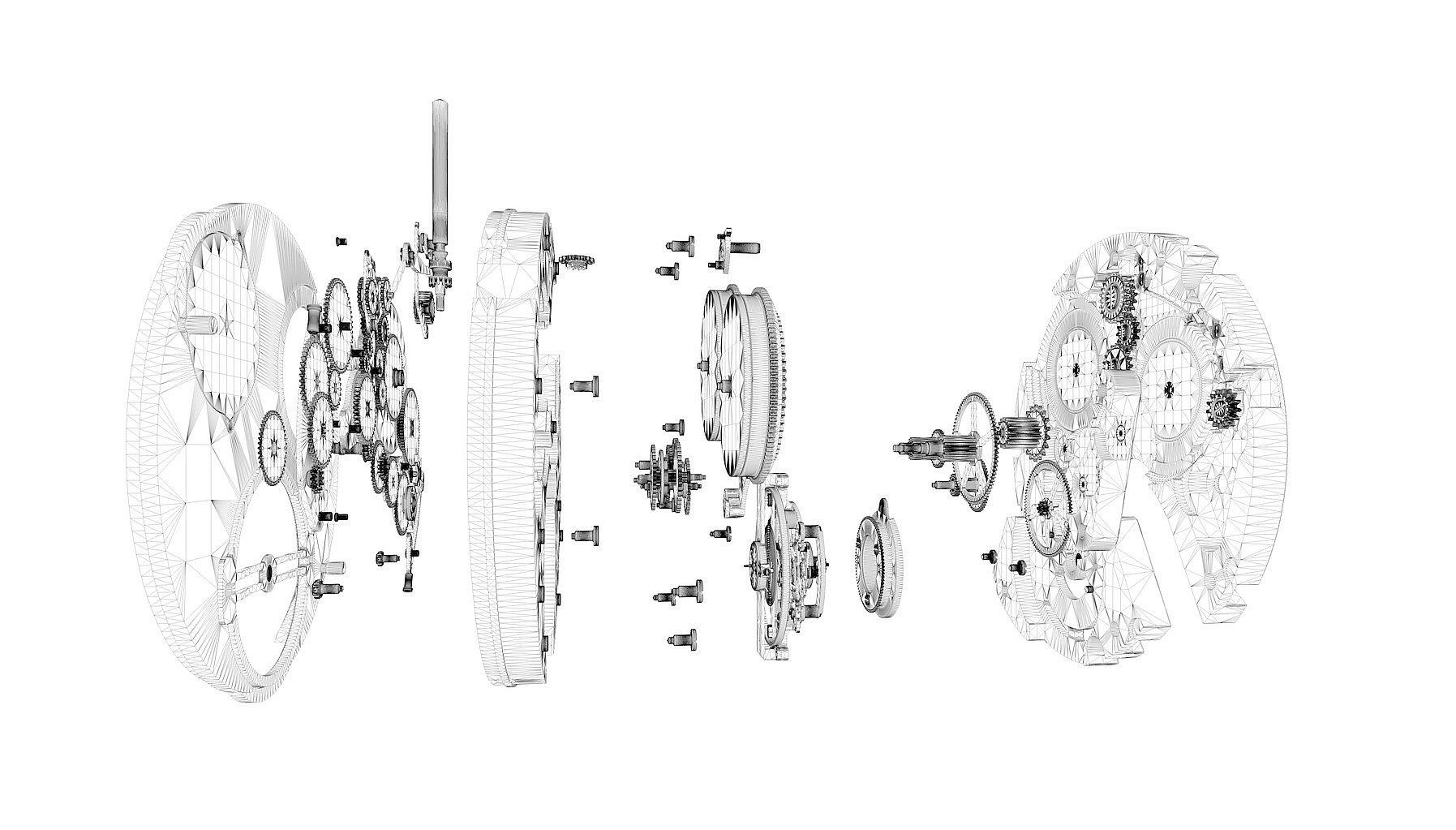

At the beginning of the ’80s I tried to launch a big watch, which is now called the Portofino. I took Germany as a test market. I went to five main retailers and they all laughed. They said nobody will ever wear a watch of this size, 45 to 46mm. So we just made about 100 pieces and stopped. But for our 125th anniversary, we returned to big watches. I said we need a watch made 100 per cent in-house. It has to be accurate for a mechanical watch, and has to be typical IWC. So we took a pocket watch movement and made the limited edition Portuguese. It was a risk, but it paid off. That also started a new trend of big men’s watches.

How did the Portofino get its name?

I’m a fan of Italy. I launched three different lines: Portofino, Venezia and Amalfi. Venezia was a rectangle one, not very successful. Amalfi was a chronograph, beautiful, quite heavy but we killed it with the price. It was our fault, we set it much too expensive, so it died. But with the Portofino, my friend Mr Blumlein said, “forget it, nobody needs a round watch with three hands because everybody has one already.” But I said we needed one because we have diver, engineer, chronograph, pilot but not one simple elegant watch. So against all odds, I said we’ll make it, and it has become probably one of the most successful lines we ever made.

Do you think the industry is more or less creative now than before?

Somebody told me there’s a new trend for white watches. I said we made in 1985 the first white watch called the Da Vinci. So it’s not so new. There are trends. You have to follow them in a way. You try to create trends, of course. Sizes, for instance. Everybody has big watch now. Perhaps in 10 years it would go a little smaller. Then with dial colour, blue is something everybody has now. At the beginning it was a special colour for platinum pieces. Funny story. There was one day when former CEO Georges Kern made a steel watch with blue dial. Then we had this internal meeting and somebody from our staff in Holland stood up and said, “who had this crazy idea to change colours?” Kern got up and said, “I did it. Do you have a problem with it?” And that was the end of the discussion. (laughs)

Vintage watches are extremely popular these days. Why do you that is so?

It’s an interesting development with vintage watches. Vintage always existed, you know. I have to admit the watch industry, in a way, neglected the vintage business. There were few specialists who dealt with antique or preowned watches, and now it’s become a big trend. So we do try to control it a bit. We take in old watches, refurbish them, check them, and certify and authenticate them. We’re getting more involved. I mean, there are some really beautiful old watches out there.

Choose one IWC watch to wear in the morning, noon and night.

This is a difficult question, there are so many nice watches. That said, I’ve been wearing the Grande Complication every day for seven years. It would be my evening and night watch. I like a good sports watch for the afternoons, and in the morning, I would wear a Portofino.

Apart from the manufacture, where would you tell someone to go to know more about IWC?

The boutiques. It’s really amazing how much the staff knows about IWC. They told me things even I didn’t know, such as information about sizes and straps. Until we started on big watches, people didn’t care how many millimetres a watch is. Now the first question they ask is how big and how many millimetres. 44 or 45? It has become very important, apparently.